still in print and available for purchase . . .

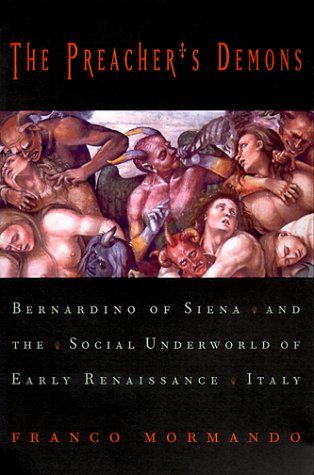

THE PREACHER’S DEMONS: BERNARDINO OF SIENA AND THE SOCIAL UNDERWORLD OF EARLY RENAISSANCE ITALY

THE PREACHER’S DEMONS: BERNARDINO OF SIENA AND THE SOCIAL UNDERWORLD OF EARLY RENAISSANCE ITALY

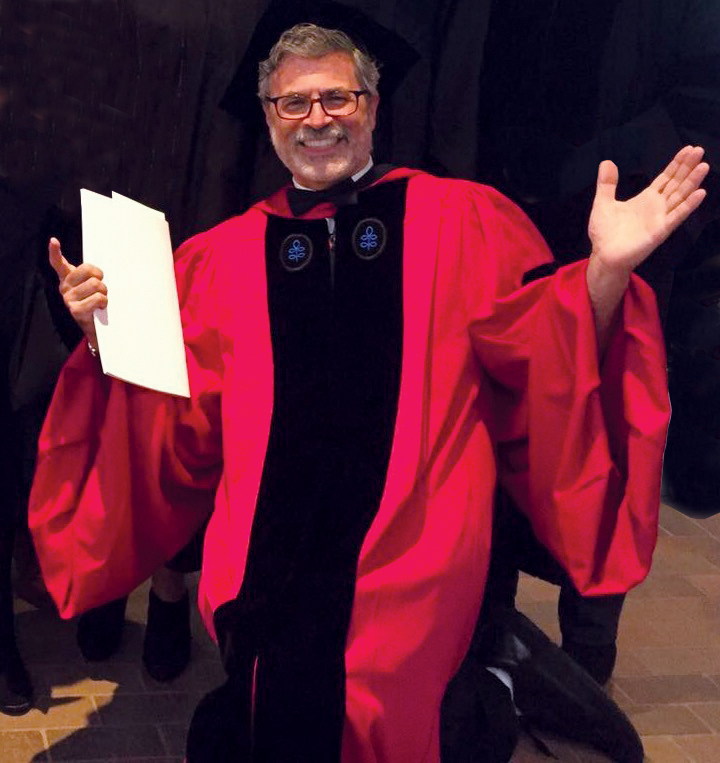

Awarded the Howard R. Marraro Prize for Distinguished Scholarship in Italian History, January 6, 2001, conferred by the American Catholic Historical Association.

Motivation for the award, as stated in January 6, 2001 News Release by the American Catholic Historical Association’s committee of judges: “because of [Prof. Mormando’s] exemplary and careful analysis of the Italian, Latin, and German sources, because of his thoughtful and balanced discussion of topics that could easily lend themselves to apologetics, invective, and/or special pleading, and because of the importance of his book for our understanding of Italian religious culture at a time when Italy was transforming Western culture in general…”

“In my Renaissance class, I have students read Franco Mormando’s excellent, The Preacher’s Demons: Bernardino of Siena and the Social Underworld of Early Renaissance Italy because it demonstrates how the ‘persecuting society’ that developed during the fifteenth century — demonizing witches, Jews, and sodomites — had a real historical impact. Laws were passed, people were rounded up and executed, and an overall hysteria was instilled local populations. Mormando’s splendid framing of these issues always proves to be a great launching pad for extended class discussions about language and the construction of sexual categories, how people with ill-informed prejudices in earlier times viewed difference, and how fear and ignorance can produce similar misunderstandings today.”

— Ben Lowe (professor of early modern European history, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton), “Including Sexuality as a ‘Useful Category of Analysis’ in College History Courses,” Perspectives on History, January 2013, p. 27 (Perspectives is the newsmagazine of the American Historical Association).

“This major study of a major but neglected figure from Renaissance Italy reveals the fanatical recklessness of Bernardino’s rhetoric especially about witches and sodomites. Franco Mormando’s conclusions rest on incontrovertible evidence, which he is the first scholar to examine in comprehensive fashion. The book, a fascinating and important contribution to our understanding of an historical epoch, is also a cautionary tale for our own, increasingly self-righteous times.”

— John O’Malley, Georgetown University, author of Praise and Blame in Renaissance Rome, The First Jesuits, and Trent: What Happened at the Council (from the dustjacket)

“Preaching is a fine but fugitive art. Sermons from the distant past, however compelling they may have been to the audiences to whom they were first adressed seldom make for gripping reading for later generations. The sermons of St. Bernardino of Siena are an exception. A ferocious and formidable rabble-rouser in his own day, his spirited attacks on the threats that he believed menaced fifteenth-century Christendom still make gripping reading, although for reasons very different from those that the preacher had in mind. Because of their power, cool, considered, and even-handed appraisals of Bernardino’s sermons are rare. Franco Mormando provides a judicious, but non-judgmental, appraisal of Bernardino’s attacks on three groups whom he considered enemies of the society of his day: witches, sodomites, and Jews.”

— James A. Brundage, Ahmanson-Murphy Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History and Law at the University of Kansas, author of Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe (from the dustjacket)

Pinturicchio, “The Glory of St. Bernardino of Siena” (1484-86), Bufalini Chapel, Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome (photo: F. Mormando)

Visual representation of Bernardino’s preaching performance

by artist Sano di Pietro (1405-81)

Sano di Pietro produced many portraits of Bernardino (indeed, Bernardino is arguably the first saint for whom we have an authentic likeness). This panel — in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Siena — shows the conclusion of a sermon by Bernardino at which time he would elevate his “IHS” tablet (icon of his new cult of the Holy Name of Jesus) for veneration by his audience. Note the segregation of the sexes and the classes (i.e., the VIPS are in the far right by themselves). So as not to intrude too much in the work day, Bernardino’s sermons began at dawn, lasting two to three hours. The pulpit and the altar are temporary structures (note the Marian image on the altar).

Though valuable as a form of visual documentation, the scene is not a full and authentic photographic account: the crowd is far too small and far too orderly and too homogeneous (e.g., where are the country folk who normally came into town for the friar’s sermons?). Bernardino at times would interrupt his sermons to scold people in the audience who were chatting or otherwise being unruly. Interestingly, several of the women are wearing the same long shawl over their head and shoulders: long, while with three blue strips towards the edge. I wonder if this identifies them as members of the same sodality?

Contemporary accounts of Bernardino’s sermon “performances” make reference to the state of near hysteria to which the friar had excited his listeners by the end of his sermon, so that the veneration of the IHS tablet seen below would have been accompanied by much shrieking and gesticulation. On some occasions, the final act of Bernardino’s “performance” would be the “bonfire of the vanities” in which people would throw their sinful objects — playing cards, cosmetics, books, etc. — for destruction.

In this view, one sees the IHS monogram — designed by Bernardino to replace devotion to the plague of political factionalism represented by civic and patrician coats-of-arms — high on the facade of Siena’s town hall. Bernardino also made wild claims about the healing and apotropaic powers of the Name of Jesus (“IHS” is an abbreviation of the Greek form of Jesus’ name).

Sano di Pietro, “St. Bernardino Preaching, Piazzo del Campo, Siena”

Bernardino continues to be a well-known, popular saint in Italy … a scene from Viterbo: