REGARDING BERNINI: HIS LIFE AND HIS ROME:

Updates are added to the top of the list (and no longer inserted into the list according to the relevant page number in Bernini: His Life and His Rome.)

Bernini: Ecstasy of St. Teresa, detail

#50. Pages 161-65: Did Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa cross a line?

I have much expanded and fully annotated the discussion of this question raised in my Bernini: His Life and His Rome in my article, “Did Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa Cross a 17th-century Line of Decorum?,” published in Word and Image, 39:4, 2023: 351-83.

Baroque putti (not by Puget)

#49. Pages 199-200: Bernini as Alexander VII’s artistic factotum and general contractor… and a note about the little known Bernini assistant, Arrigo Giardé

Among the many little artistic services rendered by Bernini to Pope Alexander VII we may now add this one, discovered in a document published in 2007 by Jacopo Curzietti: in December 1655 Bernini was paid 12 scudi for having procured for Alexander 3 small putti made of ivory sculpted by “monsù Pietro francese scultore,” whom Curzietti identifies as the very accomplished Pierre Puget (1620-94) of Marseilles (Jacopo Curzietti, p. 184, “Alessandro VII Chigi e l’arte orafa tra politica e misticismo,” in Ori nell’arte: Per una storia del potere segreto delle gemme, ed. Stefania Macioce [Rome: Logart Press, 2007], 183-84, notes 188-191, plus Appendix A, “Documenti dalla contabilità della Dataria Apostolica (1655-1667), 194-199).

However, in commenting on the transaction, Curzietti does not mention that there was yet another intermediary in this acquisition: when we go to the document itself (Appendix A, doc. I, #45, p. 195) we find that it says that the 12 scudi were “paid to Signor Cavalier Gian Lorenzo Bernini scultore, e di suo ordine à Rigo Giardè per tanti pagati à monsù Pietro francese scultore…“: paid to GLB and at his order to “Rigo Giardè.” The latter artist’s name is conventionally rendered as “Arrigo Giardé,” Arrigo being the Italianized version of Henri.

A word is in order about this near-mysterious Arrigo Giardé, who had the singular honor of living in the Bernini household from 1650 until 1660 according to the annual Easter census, the stati d’anime, published in appendix (pp. 343-45) to Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco’s biography of Bernini, L’immagine al potere (Rome: Laterza, 2001).

Though he shows up regularly in the 1650s and 1660s as rendering minor (decorative) service as stuccoist and sculptor in Bernini’s commissions (Chigi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo) and other, non-Bernini projects — as well as in police records for having been involved in public violent brawls — little is known of Giardé, who is also identified in contemporary Roman documents as an architect. We assume he was Flemish: Antonino Bertolotti in 1884 cites what he describes as Giardé’s mother’s will which gives his birthplace as Cambrai: “Margherita Martoni, ‘relicta quondam Arrighi Giardè de Cambraja;'” see A. Bertolotti, “Giunte agli artisti belgi ed olandesi in Roma nei secoli XVI e XVII. Notizie e documenti raccolti negli archivi romani. Continuazione (1),” in Il Buonarroti: Scritti sopra le arti e le lettere, Serie III, vol. II, Quaderno IV, 1884, pp. 122-132, here 125 (ed. Benvenuto Gasparoni e Enrico Narducci, Rome: Tipografia delle Scienze matematiche e fisiche). Strangely enough, however, in the aforementioned Bernini household stati d’anime census, he is identified in the 1650 and 1660 entries as a “Roman sculptor.” (In the same census, over the 10 year period his first name is also rendered as Errigo, Errico, Herrico and Arigo, while his family name is given also as Giardi.) For further contemporary documentation of Giardé, see Antonino Bertolotti, Artisti belgi ed olandesi a Roma nei secoli XVI e XVIII (Florence, 1880), pp. 39-41.

–when I wrote the above paragraph on Giardé, I was unaware of Jacopo Curzietti’s article “Una nuova attribuzione ad Arrigo Giardè e Carlo Malavista. Il monumento funebre di Alfonso Vidaschi in S. Bernardo alle Terme” (Rivista online di Storia dell’arte, 2008, n.3, pp. 69-78, published by the Dipartimento di Storia dell’Arte della Sapienza, Università di Roma, and accessible through academia.edu). Curzietti (esp. pp. 70-71) adds to our knowledge of Giardé’s career, in particular, of his work as an independent sculptor (and not merely a “scarpellino”) and of his very close relationship with the Bernini family as a trustworthy assistant even in financial matters.

#48. Page 109: Is Bernini’s Charity (on the tomb of Urban VIII) a portrait of Costanza?

Bernini, Tomb of Urban VIII: Charity

Bernini, Costanza Bonucelli (Bargello, Florence)

There is a a small debate among Bernini scholars and aficionados whether the allegorical figure of Charity on Bernini’s tomb of Pope Urban VIII is a portrait of the artist’s former lover, Costanza Bonucelli. (By the way, it has been established once and for all by the excellent research of Sarah McPhee that the correct spelling of her married surname is Bonucelli, not Bonarelli.) The real answer to the question is: It matters not what we today feel about the issue, rather what really matters is that Bernini’s contemporaries thought there was a definite resemblance. The story was so much a part of the “oral tradition” surrounding Bernini during his lifetime that over 30 years after the end of their affair, people were still spreading this piece of gossip: we know this because it shows up in the famous anti-Bernini pamphlet of ca. 1670-74, “Il Costantino messo alla berlina,” which survives at least two manuscripts in the Vatican Library, Cod. Vat. 8622 and Cod. Barb. Lat. 4331.

The latter manuscript (4331) represents a longer version of the other and was first published by Giovanni Previtali in abridged form in 1962 (Paragone vol. 145, pp. 55-58), but most recently and unabridged by Tomaso Montanari in his book, La libertà di Bernini (see below on this Update page, item #51A). In addition to repeating the “urban legend” about Costanza and the Charity figure, this pamphlet is also famous for denouncing Bernini’s Cornaro Chapel for having “dragged that most pure Virgin [St. Teresa of Avila] down to the ground,” while “transforming her into a Venus who was not only prostrate, but prostituted as well.” Our anonymous author was assuredly not alone in holding either of these two views (about Bernini’s Charity/Costanza and his Teresa of Avila): as any one who has studied the art and science of popular opinion polling or who has worked in the “Complaint Department” of a retail company knows, each single opinion that gets expressed in writing or other form represents a significant enough portion of the population to be taken seriously.

Be that as it may, on p. 109 of my Bernini: His Life and His Rome, when I said, “If you look carefully at … Charity… you will see Costanza,” I did not mean to claim that Charity was an exact portrait of Costanza, but rather that there was, in effect, what we might call a “family resemblance” between the two women, strong enough that when looking at the Charity one is likely to think of Costanza. The “family resemblance” was, more importantly, evident enough to Bernini’s contemporaries and hence the rumor was born and spread for over thirty years. Yes, the noses of the two women are not the same, but consider the following features:

- the full, round, curvaceous face of both women. (If Costanza were smiling, her cheeks would be as pronounced as those of Charity).

- their equally full, almost puckered lips.

- the strong, prominent, almost masculine, chin, with a hint of a cleft.

- the full, round, protruding, expressive eyes.

- the similar, thin eyebrows

- the same high forehead: the distance between her eyebrows and hairline is the same.

The fact of this similarity is not at all surprising: if we examine other female faces in his oeuvre, we have to conclude that Bernini, like Rubens, seemed to have had his own distinctive “female type,” representing his version of ideal feminine beauty: we see her again in his Truth Unveiled by Time. And it is not surprising, therefore, that he had a wild passionate affair with a woman whose physical appearance matched so closely that ideal type. OR was the reality the reverse? Namely, after having had his affair with Costanza, he could not help imprinting the echo of her face in the features of his subsequent sculpted females?

Bernini: Truth Unveiled by Time, detail (Galleria Borghese)

#47. Page 203ff: Bernini’s glorious transformation of St. Peter’s Square

Here’s a not well-known view of the old and not-very-attractive St. Peter’s Square before Bernini’s Colonnade (and before the addition of Maderno’s nave and facade to the basilica). The painting, executed in circa 1600, is by Flemish artist, Louis de Callery (1580-1621), Vue de la place Saint-Pierre de Rome lorsque le pape Clément VIII apparaît à la loggia après son élection en 1592. It is in the collection of the Petit Palais in Paris (Inv. PPP 04833; purchased in 1990). (information and image from Wikimedia). Seeing views of the pre-Bernini Piazza San Pietro makes one appreciate even more deeply what the artist, with what was really an economy of means (an oval of plain Doric columns), achieved in this (geometically complicated) work.

Louis de Caullery, The election of Pope Clement VIII (Petit Palais, Paris; photo: Wikimedia)

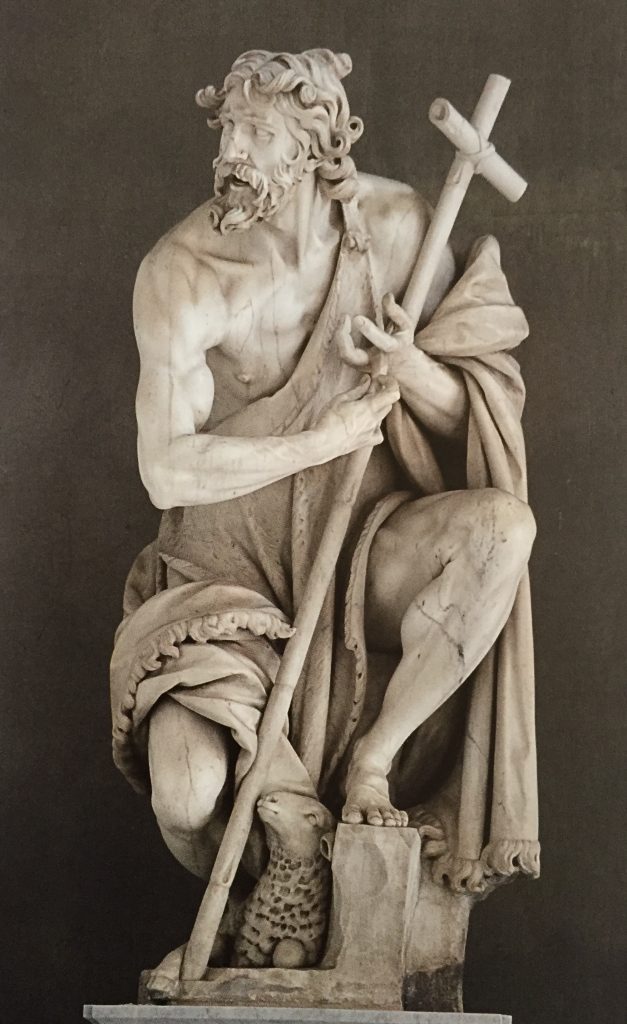

#46. Page 133: Francesco Mochi as Bernini rival

Estelle Lingo’s Mochi’s Edge and Bernini’s Baroque (London: Harvey Miller, 2017, pp. 149-151) brings to attention a little know fact, recounted by Giambattista Passeri (d. 1679) in his Vite de’ pittori, scultori, ed architetti, that adds another reason why Bernini would have not harbored benign feelings toward Mochi: according to Passeri, Mochi was commissioned in 1629 by Pope Urban VIII to sculpt a statue of St. John the Baptist to replace the one by Bernini’s father, Pietro, long installed in the Barberini family chapel in Sant’Andrea della Valle. Naturally, Bernini (Gian Lorenzo) protested (since his father was still alive when Mochi received his first payment in June of that year) and protested all the more shortly later when his father passed away (in August). As Lingo explains (p. 150), “Given Urban’s close relations with the Bernini family, it is difficult to believe that the pope initiated this project, and some scholars have argued that Mochi’s commission came from Carlo Barberini, in whose account book the documents appear, and must have been intended for another location” (even though Mochi’s finished statue is “so similar in terms of overall pose and direction of the gaze” to Pietro’s that it gives credence to Passeri’s account). In any event, Bernini prevailed and the substitution was never effectuated. Mochi’s statue is now in Dresden, having been purchased from the Chigi in 1728-28 by Augustus II, Elector of Saxony.

Mochi, St. John the Baptist, ca. 1629, Hofkirche,Dresden

For more on the Bernini-Mochi rivalry, see my edition of Domenico Bernini’s Life of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, p. 316, n. 38.

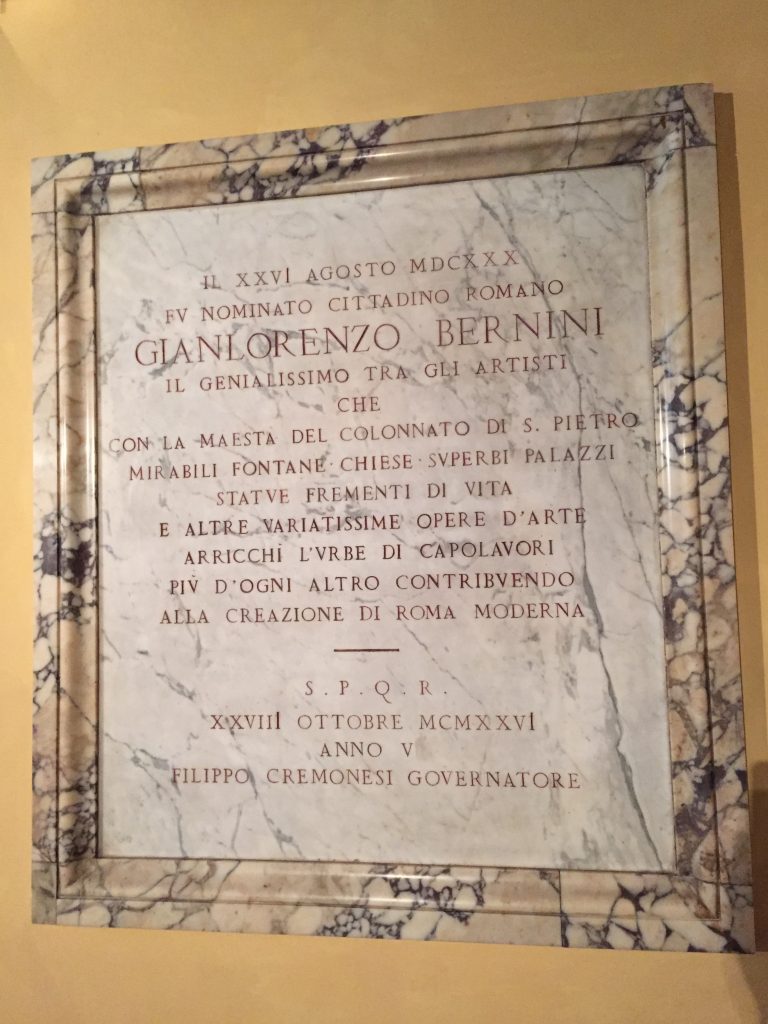

#45. Page 351: Public memorials to Bernini in Rome

To the very short list of public plaques and other memorials to Bernini in the city of Rome, we can add this one in the Musei Capitolini dating to 1926 and commemorating the fact of Bernini’s having been named a “cittadino” of the city of Rome in 1630. I wonder what the story behind this 1926 plaque is?

“Bernini Citizen of Rome” Commemorative Plaque, 1926 Musei Capitolini, Rome (photo: F. Mormando)

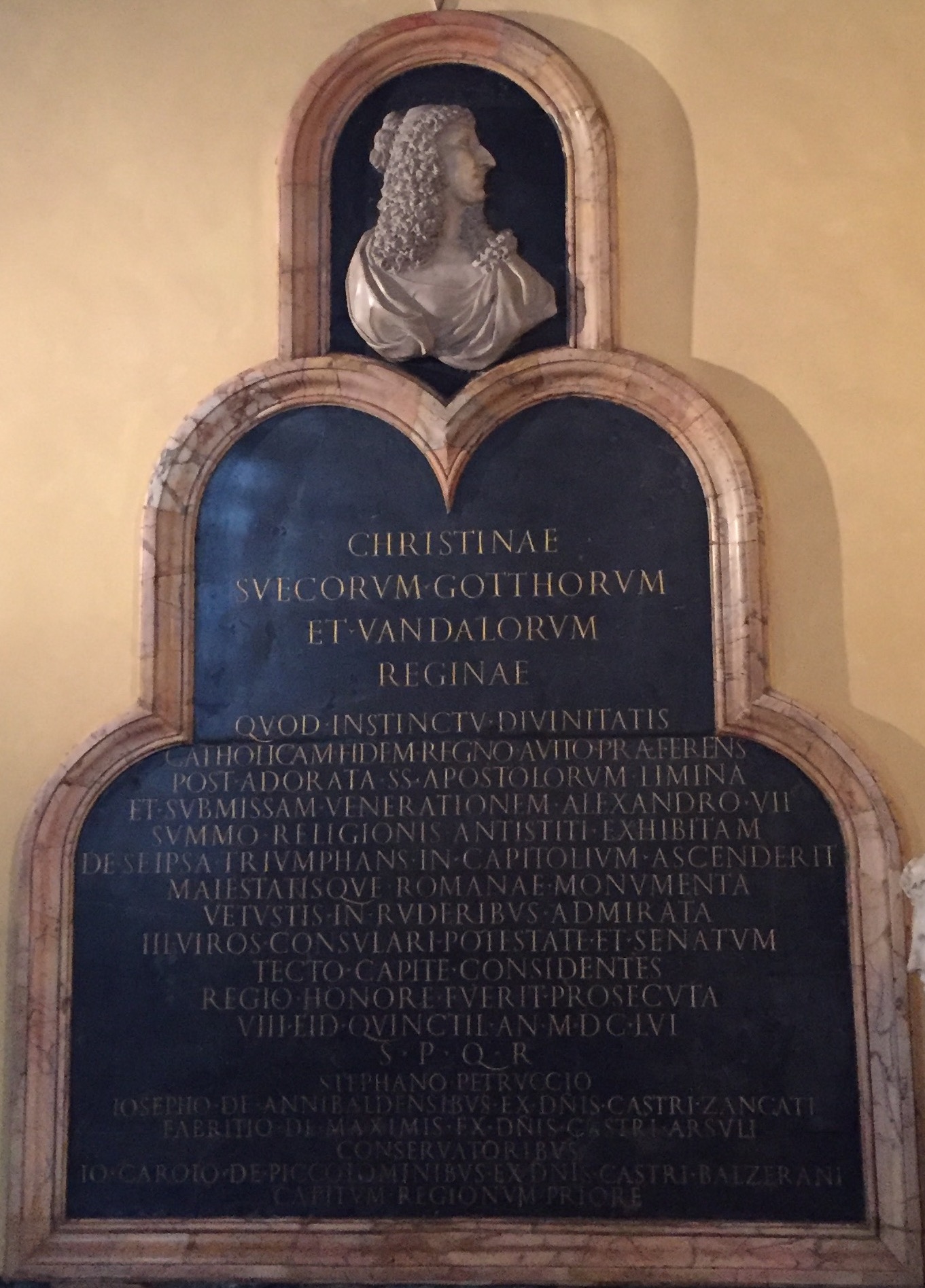

#44. Pages 218-220: Cristina’s First Official Visits in Rome, 1665

This plaque in the Palazzo dei Conservatori (Musei Capitolini, Rome), which I only recently noticed, records Queen Cristina’s official visit to the Campidoglio, right after having paid her respects to the pope:

Cristina of Sweden Plaque, Palazzo dei Conservatori, Rome (photo: F. Mormando)

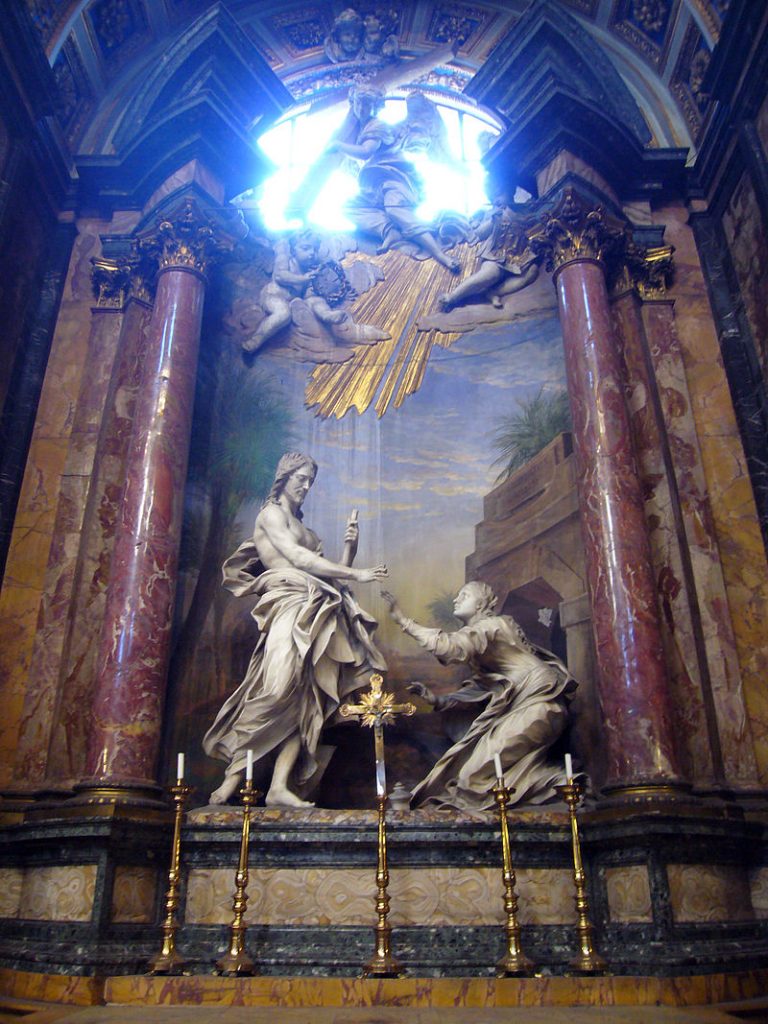

#43. PAGES 92-93: Bernini and the Cappella Alaleona (Noli me tangere statue)

Antonio Raggi (freely based on design by Bernini), “Noli me tangere,” Rome, Church of Santi Domenico e Sisto (photo: wikimedia)

In his “Gian Lorenzo Bernini e Antonio Raggi alla cappella Alaleona nei Santi Domenico e Sisto,” Nuovi Studi: Rivista di arte antica e moderna [2013] 19:181-92), Stefano Pierguidi argues for a much later date for the execution of the statue and chapel, based on compelling evidence: given a 1649-52 date by Wittkower and accepted by virtually everyone else, Pierguidi (pp. 184-85) would date its execution to at least 1663 (e.g., it is not mentioned in the second [1663] edition of Giovanni Battista Mola’s Breve racconto delle diverse opere d’architettura, scultura et pittura fatte in Rome…) and perhaps as late at 1674 (the latter date corresponds with the first securely dated reference to the statue, i.e., in Filippo Titi’s artistic guide to Rome, the Studio di Pittura, Scoltura et Architettura).

Pierguidi notes (pp. 184-85) the complete silence about the chapel or statue in the otherwise conscientious 1656 chronicle of the convent by its prioress, Suor Domenica Salamonia. Pierguidi (p. 186) is also decidedly of the opinion that Raggi, a recognized master sculptor in his own right, had much freedom in the execution of the statue, and, more specifically, in all probability did not work from a modello supplied by Bernini.

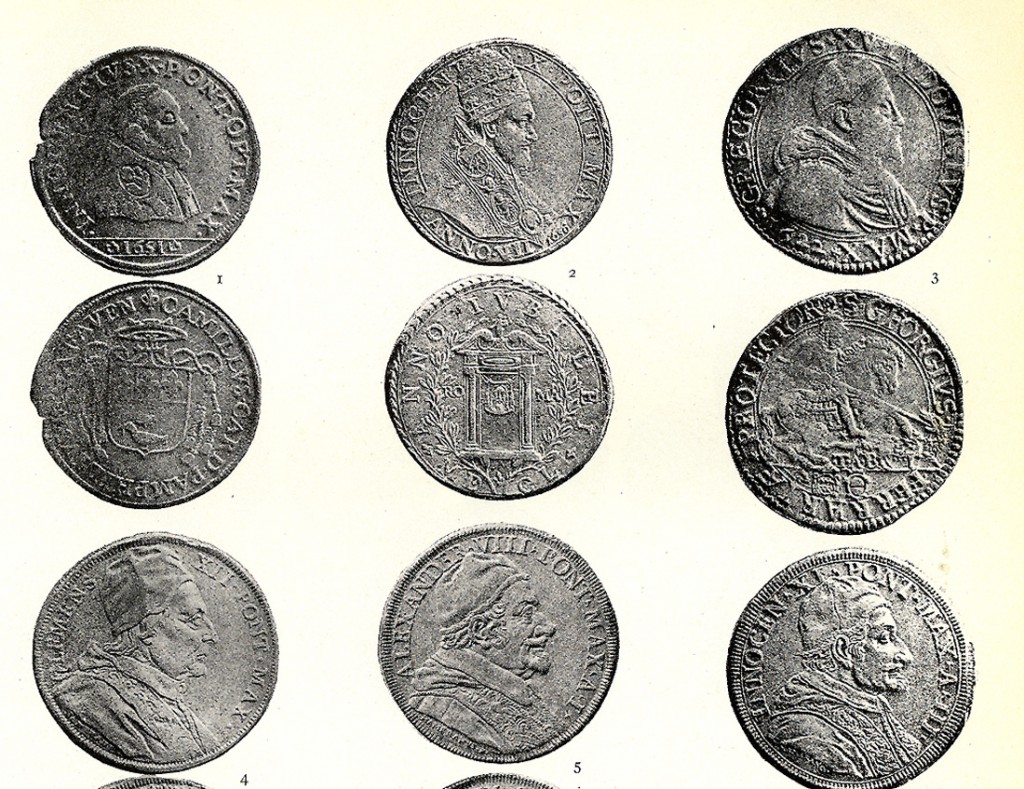

#42. PAGES XVII-XIX: MONEY, WAGES, AND COST OF LIVING IN BAROQUE ROME

For an excellent discussion of the difficulties of converting from one currency to another or measuring the value in modern terms of salaries or prices from far-away history, see the website created by university economic historians, MeasuringWorth.com.

For further data on the economy of Baroque Rome, see Painting for Profit: The Economic Lives of Seventeenth-Century Italian Painters by Richard Spear and Philip Sohm (Yale University Press, with contributions by Ago, Fumagalli, Goldthwaite, Marshall, and Morselli), especially pp. 33-40, discussing currency, incomes, food, rent, and other costs of living. The authors do not attempt a conversion from 17th-century papal scudi to modern American dollars, as I do. In any event, all that I have read or been told since writing my own preface on the subject does not change my own educated guess at such a conversion, namely, 25,000 scudi = (approximately and conservatively) one million dollars today.

An additional useful point of fact regarding the typical salaries of seventeenth-century Romans comes from Renata Ago, Economia barocca (Rome: Donzelli, 1998, pp. 8-9) who reports that the average wage of a skilled worker (“operaio specializzato“) in Rome in the 1620s was 3 scudi per month. Ago’s otherwise excellent book does not give much data by way of wages and cost of living in Baroque Rome; but on pp. 169-70, we find a couple of interesting data points: in 1627, a Roman woman living in a two-room attic appartment (rione [neighborhood] not identified) was paying 8 giulii (i.e., less than one scudo) per month (1 giulio = 10 baiocchi; 100 baiocchi = 1 scudo); in rione Regola another Roman was paying 10 scudi per year (type of apartment not identified), which amounts to a similar monthly rental cost. On a higher level of transaction (Ago, op. cit., 169), the “Illustrissimo Signor Antonio del Drago” in 1628 was renting an entire Roman patrician palazzo from Duke Cesarini for 300 scudi per year.

According to the List of Expenditures relating to the Barberini musical play (Chi soffre speri) for the Carnival season of 1639, the tailor working on the costume and/or scenery was paid 4 giulii (= 40 baiocchi; 100 baiocchi = 1 scudo) per day (Elena Tamburini, Gian Lorenzo Bernini e il teatro dell’arte, Florence: Le Lettere, 2012, p. 98).

I have come across some further salaries of Baroque Rome: in the year 1623, these were the monthly salaries of employees of the Biblioteca Vaticana: the scriptores, 5 scudi; the custodi, 7 scudi; and the Cardinale Bibliotecario, 110 scudi (source: Claudia Montuschi, “Le Biblioteche di Heidelberg in Vaticana: I Fondi Palatini,” in La Vaticana nel Seicento (1590-1700): Una biblioteca di biblioteche, ed. C. Montuschi [Storia della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, vol. 3; Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 2014], pp. 279-336, here, p. 329, note 70).

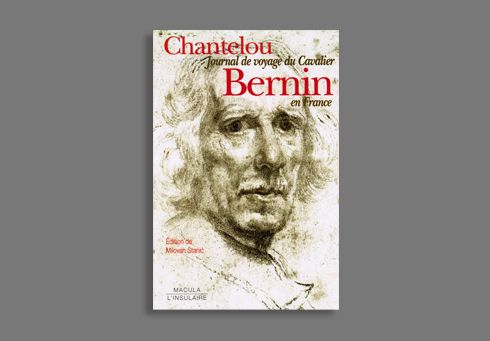

#41. PAGES 9-10: CHANTELOU’S DIARY AS PRIMARY SOURCE FOR BERNINI’S LIFE

for more information about the diary, its author and contents, see the various essays from the November 2007 symposium devoted to the diary (held at the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris) now published in the volume edited by Ferdinando Bologna, Confronto: Studi e ricerche di storia dell’arte europea, n. 10-11 dicembre 2007 – giugno 2008 (Naples: Paparo, 2009).

#40. PAGES 13-14: BERNINI, FLORENTINE OR NEAPOLITAN?

An entry in the Archivio Capitolare di San Pietro, dated May 15, 1627, that records the expense of the full-scale model of Bernini’s preliminary (rejected) design for new Veronica Pier in St. Peter’s coincidently (and without comment) reveals the failure of the artist’s attempt to pass himself off as a Florentine, when it parenthetically gives the identity of the artist in question) thus: “(inventore Equite Io. Laurentio Bernino Florentino Neapolitano)” — the adjective, “Florentine” is crossed out with one stroke and “Neapolitan” is inserted, as here reproduced (see Louise Rice,”The Pre-Mochi Projects for the Veronica Pier in Saint Peter’s,” in The Eternal Baroque: Studies in Honor of Jennifer Montague, ed. Carolyn H. Miner (Milan: Skira, 2015), 175-201, here 190, n. 34).

#39. PAGE 15: BERNINI’S DOWNPLAYING OF HIS NEAPOLITAN ROOTS

Two papers given at the 2012 Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting perhaps offer additional reasons why Bernini, throughout his life, hardly made mention at all of his birth and childhood in Naples: the Neapolitan character did not have such a great reputation in the rest of Europe, especially with regards to artistic temperament and genius:

(1) Thomas Willette, University of Michigan, “Spanish Vices and the Character of Neapolitan Artists” (Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting, 2012, Washington DC, Program: Session 20325, p. 305):

“One of Vasari’s explanations for the poverty of the arts of design in Naples is that the geography and climate of southern Italy are inhospitable to genius. That certain defects are inherent in the complexion of Neapolitans was well established. Vainglory and jealousy, exacerbated by a preoccupation with personal honor and disdain for civic virtue, are among the national traits reported by outsiders and insiders alike….”

(2) Livio Pestilli, Trinity College, Rome Campus, “The Napoletaneità of Neapolitan Artists” (Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting, 2012, Washington DC, Program: Session 20425, p. 338):

“In describing Salvator Rosa’s peculiar personality, the Umbrian Giambattista Passeri claimed the artist’s vainglorious character was a disposition common to all Neapolitans. In Passeri’s view, Rosa’s narcissism and vanity were not just ascribable to the painter’s personal character. Rather, ‘These qualities were typical national traits that he could not eradicate, since they were inherited from the local climate.’ Two generations earlier, don Pietro d’Aragona, who in 1668 had begun a radical attempt to eliminate brigandage in the Kingdom of Naples, believed banditry was an inevitable evil ‘por ser natural en el genio de la nacion.’”

Pietro Bernini, “Madonna and Child with Young St. John the Baptist,” ca. 1606, detail (Museo di San Martino, Naples)

#38. PAGES 17-18: ETHNIC COMPOSITION OF ROME

Sarah McPhee, Bernini’s Beloved, 2012, 27 (citing the research of Thomas Dandelet), mentions the interesting statistic that in early 17th-century Rome, about 25% of the city’s population was comprised by Hispanic nationals (that is, Spanish and Portuguese).

Chiesa del Sacro Cuore, Piazza Navona, Rome, formerly San Giacomo degli Spagnoli, one of the two Spanish churches during Bernini’s life (facade has been remodeled since then)

#37. PAGES 18-19 (& 175 & 204): MASSIVE POVERTY RATE IN ROME

The July 1656 census of the population of the Roman rione of Campo Marzio (a special census occasioned by a new outbreak of bubonic plague) confirms the existence of massive poverty in papal Rome. According to the census, in Campo Marzio, the heart of Rome, there were 15,543 persons divided among 3,599 households, of which households only 79 are described as “ricche” (rich) and only 1,002 as “commode” (comfortable) whereas 2,330 are classified as “povere” (poor) and 188 as miserabili (destitute). (Source: Enrico Narducci, “Artisti dimoranti in Roma nel rione di Campo Marzo l’anno 1656,” in Il Buonarroti: Scritti sopra le arti e le lettere di Benvenuto Gasparoni continuati per cura di Enrico Narducci [Rome], vol. 5, 122-26 [statistics on p. 122]).

*****

The topic of poverty — and in general, the “demi monde” — of Baroque Rome was explored in an art exhibition curated by Francesca Cappelletti and Annick Lemoine at the Villa Medici (French Academy) in Rome (Oct.7, 2014 – Jan. 18, 2015), entitled:

“The Baroque Underworld: Vice and Destitution in Rome”

“The Baroque Underworld reveals the insolent dark side of Baroque Rome, its slums, taverns, places of perdition. An “upside down Rome”, tormented by vice, destitution, all sorts of excesses that underlie an amazing artistic production, all of which left their mark of paradoxes and inventions destined to subvert the established order. This is the first exhibition to present this neglected aspect of artistic creation at the time of Caravaggio and Claude Lorrain’s Roman period, unveiling the clandestine face of the Papacy’s capital, which was both sumptuous and virtuosic, as well as the dark side of the artists who lived there.

Seicento Rome was the most lively cultural center of Europe, with a vibrant avant-garde which attracted artists from all over Europe. Many were the Italians, French, Dutch, Flemish, and Spanish who settled and made their careers in the Capital of art. In contact with this “splendid and miserable city”, as Pasolini called, they gambled with the visual codes and standards of beauty, measuring themselves against the universe of slums and dangers of nightlife, the Carnival and its licentiousness. This milieu which was both burlesque and poetic, vulgar and violent, became, for some, a central theme, and for others, an experience of life.

The exhibition features over fifty works of art created in Rome during the first half of the XVIIth century by artists from all over Europe, including Claude Lorrain, Valentin de Boulogne, Jan Miel, Sébastien Bourdon, Leonaert Bramer, Bartolomeo Manfredi, Jusepe de Ribera, or Pieter van Laer. In the Grandes Galeries, the public will discover the works of the greatest Caravaggesque painters, the major Italianate landscape artists and the Bamboccianti, painters of the bambocciate, who heralded the representation of ordinary life in Rome and the surrounding countryside. Paintings, drawings, prints from major European museums, as well as works from private collections, rarely exhibited to the public.”

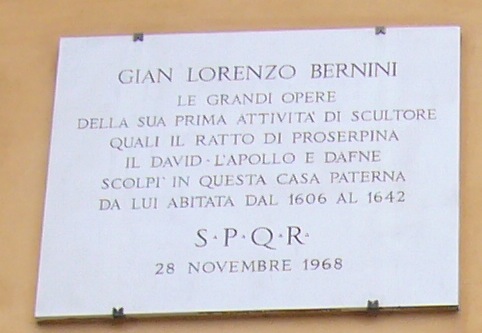

#36. PAGE 24 (caption): BERNINI HOME AT SANTA MARIA MAGGIORE

The Bernini home facing the southern side of basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore is to be found just below the word, “Maria,” in the map given on the page. The address today is Via Liberiana, 24; a plaque commemorates Bernini’s residence there.

Plaque (of Nov. 28, 1968) on Bernini Home near Santa Maria Maggiore: “The great works of his early career as a sculptor, such as the Rape of Proserpina, the David, the Apollo and Daphne, Gian Lorenzo Bernini sculpted in this his father’s house, his home from 1606 to 1642.” (photo: F. Mormando)

#35. PAGE 42: MAFFEO BARBERINI WANTED BERNINI TO COMPLETE MICHELANGELO STATUE

see note 13 on “Bernini Update 1” regarding Domenico’s Life of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

#34. PAGE 75: PAINTED PORTRAIT OF DUKE FRANCESCO d’ESTE IN BERNINI’S PERSONAL ART COLLECTION

It was only after my Bernini biography went to publication that I realized that the portrait of Francesco d’Este listed in the Bernini post-mortem inventory must be the painting done by Justus Suttermans (now lost) and sent to Bernini in 1650 or 1651 as the basis for his sculpted portrait in marble of the duke.

#33. PAGE 79: BERNINI AND THE ACCADEMIA DI SAN LUCA

For more on the Accademia di San Luca (the Academy of Saint Luke), the professional guild of Roman artists, see the website, “The History of the Accademia di San Luca, c. 1590-1635: Documents from the Archivio di Stato di Roma.” For the Bernini-related documents transcribed and uploaded thus far, do “Guided Search” under “Personal Name,” selecting Bernini from the menu of artists’ names.

#32. PAGES 91 AND 338: BONINI’S L’ATEISTA CONVINTO DALLE SOLE RAGIONI

For more on Filippo Maria Bonini and his L’ateista convinto dalle sole ragioni (Venice, 1665), cited on pp. 91 and 338 (for criticism of Bernini’s work on the Four Piers of St. Peter’s), see note 11 above in previous section on Domenico’s biography.

#32bis. Irving Lavin on Bonini (and anti-Bernini sources in general): WRONG!

By the way, the title of Bonini’s work translates as “The Atheist Converted [to the Christian Faith] by the Force of Reason Alone,” which describes the happy ending of this dialogue between an atheist and a Christian believer. However, at the same time, it contains much news and commentary on current events and issues of Bernini’s Rome, including caustic criticism of our artist. In his book Bernini at St. Peter’s: The Pilgrimage (London 2013), p. 253, Irving Lavin — who obviously never looked carefully at the book — gives the impression that it was a scandalous, heterodox work. Hardly! The author, abbate Filippo Maria Bonini, was (in 1665 at the time of the book’s publication) no less than Cardinal Antonio Barberini’s Vicar Generale for the bishopric of Palestrina. The reason it was placed on the “Index of Prohibited Books” was because of the various remarks therein that placed the “Corte di Roma” (i.e., the papal court) in less-than-flattering critical light, which, at the same time, were not gratuitously abusive or denigratory.

In citing this author, Lavin ignores the criticisms of Bernini contained in L’ateista convinto and instead discusses briefly Bonini’s treatise on the problem of Tiber flooding, while dismissing the L’ateista convinto as, in effect, the discreditable work of a hysteric malcontent that “was quickly placed on the Index of Prohibited Books,” and rightly so, Lavin appears to feel. Instead, the critical comments made in L’ateista convinto —and not just about Bernini—are echoed in any number of contemporary, respectable sources and are worthy of the attention of scholars. Betraying the limits of his knowledge of Baroque Italian — “even Homer nods” — Lavin calls the book’s title “provocative” and “scandalous” but it is neither. This treatment of Bonini is typical Lavin, who could never bring himself to take seriously any criticism of Bernini, the popes, and the other members of the religious establishment. Lavin’s apologetic, near-hagiographic view of “Roma sancta” and “Bernini sanctus” borders on the delusional.

Although representing only a brief moment in the lengthy monograph, Bernini at St. Peter’s, Lavin’s treatment of Bonini’s L’ateista convinto, let me repeat, is characteristic of his personal bias, in general, not only in this 2013 study but also in ALL of his scholarship on Bernini and Baroque Rome: by and large, his representation of Bernini, of the popes, and of Baroque Rome relies almost entirely on “official” and therefore apologetic sources, especially when describing contemporary responses to the artist, his work, or his various ecclesiastical patrons. Any unflattering or otherwise negative views are usually ignored, relegated to the footnotes, or dismissed as unworthy of attention. To cite a small but telling example in the same 2013 volume, Lavin’s claim about the edifying effect on the populace of the piety of Pope Alexander VII on Corpus Christi day has as its primary source none other than “the pope’s friend Sforza Pallavicino” (p. 167), the same Jesuit sycophant who wrote the entirely pro-papal History of the Council of Trent and who was raised to the purple by the same Alexander VII. Hardly an impartial, reliable eyewitness. Lavin does quote diarist Gigli to corroborate Pallavicino; nonetheless, his unapologetic citation of Pallavicino seems naïve on the part of a well-seasoned scholar.

About the same Pope Alexander, however, Lavin is unable to ignore the unflattering views of Roman courtier Lorenzo Pizzati, made famous by Richard Krautheimer’s Rome of Alexander VII (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987). In Bernini at St. Peter’s: The Pilgrimage (pp. 303–6) — and for the third time in his multi-volume larger work, Visible Spirit of which this 2013 study is volume 3 — Lavin attempts to at least partially refute Pizzati’s charge — one shared by many a contemporary and by much of posterity—that in his vast expenditures to build a more magnificent Rome, Alexander callously neglected the urgent needs of his suffering subjects. Lavin’s attempted refutation—in all three redactions—is unconvincing.

This predilection for official sources is also true of Lavin’s exposition of the symbolic meaning—the concetto—of Bernini’s works which occupies most of this volume: Lavin is primarily concerned with what Bernini and his patrons intended the viewers to understand and how they were supposed to respond spiritually and emotionally, namely, in a properly orthodox and pro-papal fashion. There is nothing wrong with this choice of point of view or subject matter. However, a steady diet of this kind of scholarly fare inevitably produces results that are highly abstract and divorced from 4 reality. After years of reading the unofficial sources — private diaries and letters, avvisi, diplomatic correspondence, police chronicles, court trials — I have come to doubt that many contemporary viewers responded to Bernini’s works in the intellectually proper and spiritually orthodox manner intended by the official program.

In any event, one must balance the picture by firmly contextualizing Bernini and his work in the fully three dimensional, at times dark and dirty and gritty, everyday reality of Baroque Rome, even if it means speaking inconvenient truths about “Roma sancta” and “Bernini sanctus.” To say this, however, does not diminish the enduring, monumental accomplishments of Lavin’s work—his permanent place of honor in the pantheon of Bernini scholarship is firmly assured. It is simply to caution that, just like the bee that produces its sweet honey—to use a favorite Barberini image—by collecting pollen from a wide host of different plants, so too must we arrive at our understanding of Bernini and Baroque Rome through a healthily diverse gathering of data from all available sources and points of view.

The former convent of SS. (Sante) Rufina e Seconda, Via di Lungaretta, Trastevere, Rome, seen from Piazza di Santa Rufina (photo: F. Mormando)

#31. PAGE 94: BERNINI’S TWO DAUGHTERS WHO ENTERED THE CONVENT

This fact is mentioned in Domenico’s biography of his father (p. 53); the women in question are Agnese and Cecilia, who were sent to the convent, respectively at the tender ages of 15 and 13 (judging from the years in which they disappear from the annual family census).

The convent in question, SS. (Sante) Rufina e Seconda in Trastevere, was a community of religious women, the Oblate Orsoline, following the Rule of Saint Ursula, who took no vows and were not confined to the property by the rule of cloister as was more typical of nuns and religious sisters at the time (later in the century all Ursuline convents were slowly forced by the papacy to conform adopt the cloister rule).

The community was founded by two charismatic French aristocratic women, Françoise de Montjoux and Françoise de Giurcy, during the pontificate of Pope Paul V Borghese. Their residence and church in Trastevere (Via di Lungaretta) was built by Camilla Orsini Borghese on the foundations of what was believed to be the old Roman residence of the early Christian martyrs, Rufina and Seconda, and included a medieval church, whose bellower still survives today (see photo).

There is not much bibliography on the community (which died out in the 18th century): in addition to Filippo Bonanni’s Ordinum religiosorum in ecclesia miltanti catalogus, v. 2, # 103, cited in my note, see Pierre Hélyot and Maximilien Bullot, Histoire des ordres religieux, vol. 4, Paris, 1715, pp. 229-32, Suite de la Troisieme Partie, Chap XXXI. See also Ernesto Iezzi, Studio storico della chiesa e del monastero delle SS. Rufina e Seconda in Trastevere, Rome: San Nilo, 1980. See also the section on the Ursulines of Rome in Gaetano Moroni’s Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica, within the entry on the “Orsoline.”

Habit of the Ursulines of Santa Rufina, from Bonanni, “Ordinum religiosorum in ecclesia militanti catalogus”, v. 2, #103.

#30. PAGES 99ff: BERNINI’S MISTRESS, COSTANZA “BONARELLI” (more properly, BONUCELLI)

With the publication of Sarah McPhee’s excellent Bernini’s Beloved: A Portrait of Costanza Piccolomini (Yale UP, 2012), we now possess much new information about the hitherto mysterious Costanza and her life before and after the violent affair with Bernini. Very little of new is communicated about Bernini or his works (except for the author’s sensitive reading of the Costanza bust as a work of art and an expression of Baroque feminine allure). Note that, as the primary source documentation that McPhee publishes in appendix, Costanza’s married name was legally and without a doubt “Bonucelli,” and not “Bonarelli,” as usually rendered in past literature. Yet, she usually referred to herself by her maiden name, Piccolomini, as she is named by Filippo Baldinucci in the catalogue of Bernini’s works appended to his 1682 life of the artist.

Some further additions and corrections to the record, provided by McPhee’s new book:

1. Costanza was living in the Vicolo Scanderberg closer to the center of town (her house and her street are still extant) at the time of her affair with Bernini, not in the Santa Marta neighborhood near St. Peter’s, as previously believed and as reported in my book (p. 102; see McPhee, 37 and 216, n. 3).

2. Unlike most women of her age, Costanza could read and write, as we know from a surviving letter in her hand (McPhee, 59-60). On the other hand, Bernini’s mother, Angelica Galante (as I suggest on p. 101) was illiterate, for as McPhee points out (p. 59) she had to sign her last will and testament with a cross, not a real signature.

3. Until now we knew nothing of what happened to Costanza as a result of the affair. Did she suffer any consequences, legal or otherwise? We now know answers to such questions: see McPhee, 52ff. Costanza’s husband, Matteo Bonucelli (the artist and Bernini workshop collaborator) apparently did not denounce her to the authorities, it was some unnamed eyewitness or neighbor. She suffered imprisonment for her crime and probably other punishments, as McPhee, 54, describes: “For women there were prescribed rituals of public humiliation and mandatory confinement. If Costanza’s punishment followed the legal course [as it would seem], she was whipped, shorn of her famous locks, and sent to the Casa Pia [at Santa Chiara, behind the Pantheon] to await her husband’s forgiveness.” It is certain that Costanza suffered a painful four-month period of imprisonment at Santa Chiara, as we know from a plea written in her own hand sent from there. (She mentions hunger and other deprivation, her husband refusing to send her food and other forms of succor). Costanza’s plea to the Governatore di Roma was heard and her release was approved in early April 1639.

4. Contrary to what I report in my biography (p. 105), Costanza did not voluntarily leave a post-mortem bequest to the convent of the Convertite: by law all female “criminals” of her type (“wayward women”!) were obliged to leave one-third of their estate to the Convertite, which is one of the ways in which that establishment maintained itself financially.

5. The destiny of Bernini’s bust of Costanza after the end of their affair: in reality, as McPhee points out (see her summary discussion of the question on pp. 217-18, n. 35), the documentation regarding the post-affair vicissitudes of the Costanza bust is — once again in Bernini scholarship — frustratingly incomplete and hence we cannot with complete certainty and thoroughness reconstruct this piece of Bernini history. We know for certain that by November 2, 1646 the bust was in the Medici granducal collection in Florence, seen there by a French visitor to the gallery, Balthasar de Monconys (Montanari, 2009, p. 329 in the exh. cat. I marmi vivi). What is not certain is how it got there: the report by Montanari (and repeated by me on p. 109) that it had been given as a gift by Bernini to Cardinal Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici comes from an anonymous contemporary recorded among the notes gathered by Florentine biographer Filippo Baldinucci while he was researching his Bernini biography (published in Florence 1682). However, as McPhee mentions, there is no record of the gift in the cardinal’s inventories, where one would expect to find it.

At the same time, we have a letter dated July 18, 1640 from Francesco Mantovani, the Roman agent of the Duke of Modena, reporting that the Costanza bust was going to be sent to Modena as a gift to the duke from Monsignor Annibale Bentivoglio, to be delivered by Donna Mathilde Bentivoglio (who, we know from an avviso, departed Rome for Modena on July 21). McPhee does not say whether the inventories of the ducal collection in Modena confirms receipt of the bust, or if indeed any other document confirms arrival of the bust in Modena. Some scholars (Zanuso and Zikos) suggest that Cardinal Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici may have instead received the bust from the same Annibale Bentivoglio who was not only a relative of his but also the papal nunzio (ambassador) to the Medici court of Florence.

********

In any case, my point (p. 109) that Bernini’s poor wife, Caterina, had to endure the sight and memory of he husband’s former mistress, Costanza, in her very own home after her marriage to the artist remains valid: not only did Bernini still have in his studio at home his double painted portrait of Costanza and himself but the terracotta modello (presumably full-size and in final state of execution) of the Costanza marble bust (seen there by Antonio Ferragallo as he mentions in his Jan. 25, 1641 letter to Cardinal Jules Mazarin. However, if contrary to the Mantovani letter of 1640 stating that the bust was being sent to Modena, the bust never made it to Modena, the Costanza bust seen by Ferragallo could have been the marble original and not the terracotta modello.

Unfortunately in reporting the several busts he saw in Bernini’s studio, Ferragallo does not distinguish between marble originals and terracotta modelli; some of the busts he saw, except perhaps Costanza, had had to have been in fact terracotta modelli, since the marble originals had long been delivered to their intended recipients). In the 1681 inventory of Bernini’s possessions compiled just a couple of months after his death, there is no specific mention of the Costanza bust in marble or terracotta; however, the “testa di donna” (medium not specified but presumably a sculpture) on display right next to Bernini’s self-portrait in the “Prima stanza contigua all’Anticamera” may be in fact the Costanza bust modello (cc.504v in the original document; p. 255 in the published version in Martinelli, 1996, L’ultimo Bernini).

Church of San Tommaso in Parione, where Bernini wed Caterina Tezio, one year after the fiery end of his affair with Costanza Bonucelli (photo: F. Mormando)

S. Tommaso in Parione, Rome, interior (photo: F. Mormando) According to Michael Erwee, The Churches of Rome 1527-1870, vol 1, p. 670 (London: Pindar Press, 2014), all the funerary monuments currently in the church date to the 19th century, during which the church interior was twice restored, obliterating — it would appear — any trace of the tombs or monuments of the family of Eugenia Valeri, Bernini’s mother-in-law who had burial rights to the church in the 17th century.

#29. PAGE 116: EXTINCTION OF THE BERNINI FAMILY NAME

Virtually all the Italian scholars (most notably, Ameyden-Bertini, Storia delle famiglie romane, 1910-14 ed.) originally consulted by me and who discuss the ultimate destiny of the Bernini family claim that Prospero Bernini (d. 1858) was the artist’s last direct descendant (through Bernini son, Paolo). This is incorrect: it would be more accurate to say “last direct descendant” on one section of the male line of the family, since other Bernini son, Domenico Stefano had heirs, and presumably at least one (if not all three) of Bernini’s three married daughters, Angelica Bernini Landi, Maria Maddalena Bernini Luccatelli, and Dorotea Bernini de Filippo, produced heirs. (I have received an email from one Italian American who claims descent from Bernini through one of these female lines, according to his family oral tradition.)

At present, the Forti family of Rome (inasmuch as they are descendants of the Concetta Caterina Galletti mentioned on this page of the biography) claim the title of “Bernini’s descendants” (one of the males of the family has legally inserted “Bernini” into his last name). Augusto Forti, who wrote for the Strenna dei Romanisti and who died in 1984, was a member of this family.

Besides Paolo, Bernini had one other married son, Domenico Stefano (his biographer) who produced 3 heirs, Giovanni Lorenzo, Caterina, and Angela. Now, thanks to the research of Rosella Carloni published in her extremely well-documented book, Palazzo Bernini al Corso: Dai Manfroni ai Bernini storia del palazzo… (Rome: Campisano, 2013), we know much more about Domenico’s descendants.

On page 117, Carloni publishes the genealogical tree of Domenico’s branch of the family which indicates that the aforementioned Giovanni Lorenzo had eleven children (Carloni does not give information about Angela’s children; the other daughter, Caterina became a nun; there was also another child (in fact, the first of the 4 children), Luigi, who died very young in 1705.

See page 111 of Carloni’s book for a summary genealogical tree of patriarch-artist Gian Lorenzo’s family (down to the Forti family of the present time), and page 116 for the descendants of his great-grandson, Mariano (1734-1789), son of Prospero (1694-1771), who was child of Paolo Valentino (1648-1728) and who married the aristocrat, Ortenzia Manfroni and moved the Bernini family to the Manfroni palazzo on the Corso, which then became known as Palazzo Bernini.

Palazzo Bernini on the Corso, Rome, between Via Frattina and Via Borgognona (photo: F. Mormando; “Ottico” sign has since been removed)

#28. PAGE 120: CARDINAL ANTONIO BARBERINI’S SEXUAL LIAISON WITH CASTRATO MARC’ANTONIO PASQUALINI

“Considering how much participants would have wanted to hide their activities, the number of documented liaisons between noblemen and castrati is surprising. Marc’Antonio Pasqualini’s intimacy with Cardinal Antonio Barberini [Jr.] in the 1640s is well known: contemporary testimony leaves little doubt tht the cardinal’s ‘veritable passion’ extended to more than Pasqualini’s beautiful voice.” — Roger Freitas, Portrait of a Castrato: Politics, Patronage, and Music in the Life of Atto Melani (Cambridge University Press, 2009) p. 127.

For Andrea Sacchi’s large, allegorical portrait of Pasqualini mentioned on the same page (120), see the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s entry on the painting in its collection.

#27. PAGES 127-28: BERNINI’S SLY MANEUVER TO OBTAIN ORATORIAN RENTAL PROPERTY (1640)

This episode is discussed in Chapter 2, pp. 127-28 of the biography, based upon the account given by Russo in the 1976 issue of Strenna dei Romanisti. Another account, based on the same archival documents, has been published by Lothar Sickel: “Virgilio Spada im Streit mit Gian Lorenzo Bernini: Eine merkwürdige Episode in der unbekannten Geschichte des Palazzo Cybo,” in Ordnung und Wandel in der römischen Architektur der Frühen Neuzeit: Kunsthistorische Studien zu Ehren von Christof Thoenes, eds.Hermann Schlimme and Lothar Sickel (Munich: Hirmer, 2011), pp. 215-34.

As far as Bernini is concerned, no significant new details are reported by Sickel that had not already been reported by Russo (who is not cited by Sickel), except to identify the property in question as the Palazzo Cybo and the “Cardinal Barberini” who intervened on Bernini’s behalf (with a payment of 50 scudi) as Cardinal Antonio, Junior. Sickel does, however, publish in appendix the texts of all the relevant documents and provides extensive information about Palazzo Cybo.

Sickel also reproduces a contemporary portrait of Virgilio Spada, Bernini’s Oratorian opponent and writer of the original memorandum about this episode, located in the Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia, Rome. For more on Virgilio and the Spada family, see the website prepared by a Spada descendant:

Sickel also reproduces a contemporary portrait of Virgilio Spada, Bernini’s Oratorian opponent and writer of the original memorandum about this episode, located in the Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia, Rome. For more on Virgilio and the Spada family, see the website prepared by a Spada descendant:

#26. PAGE 129: ANOTHER OF BERNINI’S RARE TRIPS OUTSIDE ROME: CIVITAVECCHIA

An article by Francesco Petrucci points out overlooked references in Pope Alexander VI’s diary to the trip (of at least three days) that Bernini took to the papal port of Civitavecchia in mid-January 1662 to inspect the nearly terminated construction of the Arsenal there, a work of his design. Until now, scholars have believed that this was a commission that Bernini simply executed “from afar,” without actually having seen the work. (Note that Bernini’s arsenal was destroyed by bombing during World War II, on May 14, 1944). See F. Petrucci, “Un dipinto ritrovato e alcune considerazioni su una perduta architettura berniniana: ‘L’Arsenale di Civitavecchia” di Viviano Codazzi,” in La festa delle arti: Scritti in onore di Marcello Fagiolo per cinquant’anni di studi, eds. Vincenzo Cazzato, Sebastiano Roberto, e Mario Bevilacqua (Rome: Gangemi, 2014): vol. 2, pp. 396-401; p. 396 for the 1944 destruction; p. 398 for Pope’s diary on Bernini’s trip).

#25. PAGE 135: LIST OF BERNINI’S WORKS FOR THE SPANISH

To the list given on this page of Bernini’s Spanish-related works must be added his design for the tomb of Spanish Cardinal Domingo Pimentel, O.P (died 1653), who served in the important role of “Cardinal Protector of the Reign and Affairs of Spain” in Rome. The tomb is located in a dark corner of the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, placed against one of the walls in a corridor leading to the rear entrance of the church to the immediate left of the sanctuary.

Though the design is entirely Bernini’s, it was executed by his close assistants Giovanni Antonio Mari, Ercole Ferrata, and Antonio Raggi. Bernini was constrained by the very shallow corridor space allotted to the tomb — hence it is very difficult to photograph — but once again the artist triumphs over his handicaps, for the tomb appears much more substantial in depth than it is in reality: another clever baroque deception. The design clearly relates to (and in fact initiates) a series of similar Bernini tombs that will culminate in his monument to Pope Alexander VII in St. Peter’s. This work is not mentioned by Domenico Bernini, but does appear in the appended catalog of Bernini works in Baldinucci’s biography.

Bernini (design), Tomb of Cardinal Domingo Pimentel, Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome (photo: F. Mormando)

For more on Bernini and the Spanish:

see the Prado exhibition, “Bernini’s Souls: Art in Rome for the Spanish Court” (Nov. 6, 2014- Feb. 8, 2015)

The published catalogue is entitled: Bernini: Roma y la Monarquía Hispánica

edited by Delfin Rodriguez Ruiz (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2014).

Publisher’s Summary: “The complex diplomatic and political relationships between Rome and Spain were reflected in the commissions Bernini received both from Spanish patrons in Rome (including key figures such as the Duke of el Infantado, Cardinal Pascual de Aragón and the Marquis of Carpio) and from the Spanish monarchy. These commissions particularly related to the fact that Philip IV wished to be represented in diplomatic, religious and political terms in Rome, funding projects in some of the city’s most important churches such as San Pietro and Santa Maria Maggiore just as he did at El Escorial and the Real Alcázar in Madrid.

The exhibition revolves around three sections that illustrate Bernini’s complex relationship with Spain and, at the same time, provide a virtual synthesis of his own development as a multi-faceted artist, based on a rich itinerary that stretches from some of his grand architectural and urban projects to his chapel scenes and sculptures, not to mention his fountains, paintings and drawings for other projects, both ephemeral and festive, decorative and luxurious.”

Cat. entry #7 (pp. 92-93) of the Prado catalog is a little-known Spanish eulogy in honor of Bernini, the Elogio de el Cavallero Juan Lorenzo Bernini, by an anonymous Spaniard who, however, had personal familiarity with Rome and Bernini’s life and career, dated ca. 1682-85. I have read the Spanish “Elogio”: directly derived from Pierre Cureau de La Chambre’s Eloge du cavalier Bernin, the author adds a couple of further, small (and not terribly revealing) details to La Chambre’s text. The catalog editor claims (p. 92) that “[t]his brief and succinct manuscript document represents, without a doubt, one of the most vivid literary contributions on the part of Hispanic artistic culture to the reception and posthumous fortune of Bernini in Spain.”

First page of the “Elogio de el Cavallero Juan Lorenzo Bernini” (Biblioteca Publica de Tarragona, mss. 177, 4 fols.)

#24. PAGE 80, LINE 26: Typographical error: for “Italy,” read: “Rome.”

#23. PAGE 150: BERNINI’S CAREER IN THE EARLY YEARS OF THE REIGN OF THE HOSTILE POPE INNOCENT X: A NEW 1647 COMMISSION IN THE LATERAN

Yet another reminder that during the early years of the reign of the anti-Barberini (and thus anti-Bernini) Pope Innocent X Pamphilj — that is, before the Spring 1648 reconciliation between pope and artist with the granting of the Piazza Navona Fountain commission — Bernini did not suffer total exclusion from important papal projects is the newly publicized fact that in Spring 1647 Bernini was commissioned to sculpt two statues (Sts. Luke and Bartholomew) for the niches of the nave of the Basilica of San Giovanni Laterano, which was undergoing major renovations by Borromini, under the supervision of Virgilio Spada (the pope’s deputy in matters of art and architecture). This was a major project, involving all the eminent sculptors of Rome. We know of this project and Bernini’s commission from the papers of Virgilio Spada.

For reasons unknown Bernini never completed the statues, but we have several drawings (in Leipzig) and one clay modello (in the Museo di Roma) attesting to his preparatory work on the statue of St. Luke. For this see: Tomaso Montanari, “Bernini in Laterano: Una nuova lettura per sette disegni berniniani a Lipsia,” In Dessins de Sculpteurs, II: Quatrièmes rencontres internationales du Salon du Dessin, 25 et 26 mars 2009, ed. Cordelia Hattori (Société du Salon du Dessin, 2009): 69-78.

#22. PAGE 152: THE MAN BEHIND POPE INNOCENT’S ABRUPT DECISION TO TEAR DOWN BERNINI’S BELL TOWERS AT ST. PETER’S

As mentioned on this page, Domenico Bernini claims that it was ” a certain minister of [Pope Innocent’s], ill-intentioned toward the Cavaliere and likewise provoked by Borromini” who is to blame for the puzzling, abrupt decision on the part of the pope to completely tear down the bell towers. This passage is usually understood to refer to Virgilio Spada, even though the extant documentation does not prove at all that Spada was particularly “ill-intentioned” toward Bernini (Bernini, nonetheless, believed him to be so, as I mentioned on this same page.) However, it should be mentioned — as does Sarah McPhee, Bernini and the Bell Towers, 167-170 — that the Modenese agent in Rome, Francesco Mantovani, believed that the man behind the decision was actually cardinal-nephew, Camillo Pamphilj, son of Donna Olimpia, who was furious at Bernini’s satire of him in the Carnival play that the artist staged for Camillo’s mother Olimpia in early Feburary 1646. Mother and son did not get along at all.

Though discussing this possibility, McPhee does warn that Mantovani’s report “must be considered with caution.” That caution disappears in Eleanor Herman’s 2008 Mistress of the Vatican: The True Story of Olimpia Maidalchini (pp. 193-95), who simply reports as fact that Camillo was the culprit here. Herman took her information, second-hand, from Jake Morrissey’s Genius in the Design (pp. 165-67) but Morrissey does add a word of caution too: “when the pope decided, perhaps goaded by his nephew, to have the bell towers demolished.”

I am entirely disinclined to believe that Pope Innocent would be persuaded in such a momentous decision by his ne’er-do-well nephew for whom he did not have much affection or esteem: as even Herman herself points out (p. 152) in another context, “But Camillo, Innocent knew, was a thoughtless ditherer.”

#21. PAGES 159-61: BERNINI’S FAMOUS BEL COMPOSTO

In these pages, I describe Bernini’s Cornaro Chapel as an example of his “famous bel composto” (“beautiful whole”). I am here employing the term in the way it has been used by modern art historians (popularized by Irving Lavin in 1980) to refer to Bernini’s creation of a complex work of art (e.g., a chapel) in which multiple forms of art (painting, sculpture, architecture) are expertly employed together, blending seamlessly with each other so as to create an aesthetically unified, integral whole. The term comes from Filippo Baldinucci’s Life of Bernini (in Domenico Bernini’s Life of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, it is called the “maraviglioso composto“).

But, in fact, as I discuss in the Introduction to my 2011 edition of Domenico’s biography, pp. 46-49, summarizing recent scholarship on the question (by Montanari and Delbeke), that modern meaning of the term is NOT found in or can be inferred from either Baldinucci or Domenico or any other primary source. Baldinucci uses the term to refer only and specifically to Bernini’s painterly approach to his architecture, whereas Domenico (to the extent that one can decipher his meaning) refers to the blending of the forms of art within Bernini’s own mind.

#20. PAGE 204: OPEN SEWER RUNNING THROUGH THE CENTER OF ROME

For a description of this sewer, the “Chiavica di San Silvestro,” finally covered up by Pope Pius V in 1571 (as one of his many hydraulic improvement projects), see Katherine Rinne, “Urban ablutions: cleansing Counter-Reformation Rome,” in Rome, Pollution and Propriety: Dirt, Disease and Hygiene in the Eternal City from Antiquity to Modernity (Cambridge University Press for the British School at Rome, 2012), p. 197 (article is 182-201): “The Chiavica di San Silvestro, an open drain that ran through the Campo Marzio, had been a notorious health hazard since at least the fifteenth century. It ran for almost two kilometres from the Trevi Fountain to the Tiber…”

#19. PAGE 208-11: ORDINARY ROMANS FORGOTTEN IN THE “RENOVATIO ROMAE“

In Chapter 4, the point is made, citing contemporary complaints, that much of the restoration and aggrandizement projects of the papal Renovatio Romae of the early modern period did not benefit the ordinary citizens of Rome. The above-cited Waters of Rome by Katherine Rinne, page 155, confirms this observation, citing the case of the many new fountains:

“The civic fountains that ornamented Rome in the early 1620s were unequalled by those in any other European city for centuries to come. Alive with impressive jets, abundant sprays, rushing cascades, spangled rains, and swirling pools, these fountains attracted wide attention. They impressed visiting dignitaries and pilgrims, increased the prestige of the city, and burnished the reputations of the popes who had sponsored them. Yet, even a cursory glance at their uses shows that provision was rarely made for day-to-day needs. In fact, they appear to have been relatively useless for average Romans who needed a dedicated drinking supply for themselves and their animals; water for domestic tasks such as cooking, bathing, irrigating kitchen gardens, and washing clothes; or a source of water for industrial procedures like manufacturing paper or wool cloth.”

Related to this observation is the statistic cited by Rinne, page 181, that by 1623 80% of the aqueduct water supply of Rome was claimed by cardinals, nobles, monasteries, and charitable organizations.

#18. PAGE 209: LORENZO PIZZATI’S URBAN IMPROVEMENT SUGGESTIONS

For a detailed examination of Pizzati’s suggestions, now see Dorothy Metzger Habel, “When All of Rome Was Under Construction”: The Building Process in Baroque Rome (Penn State UP, 2013), pp. 133-68.

#17. PAGE 212: THE SCALA REGIA

The upper portion of Bernini’s Scala Regia is now a public passageway for those leaving the Sistine Chapel and going the most direct route to St. Peter’s Basilica:

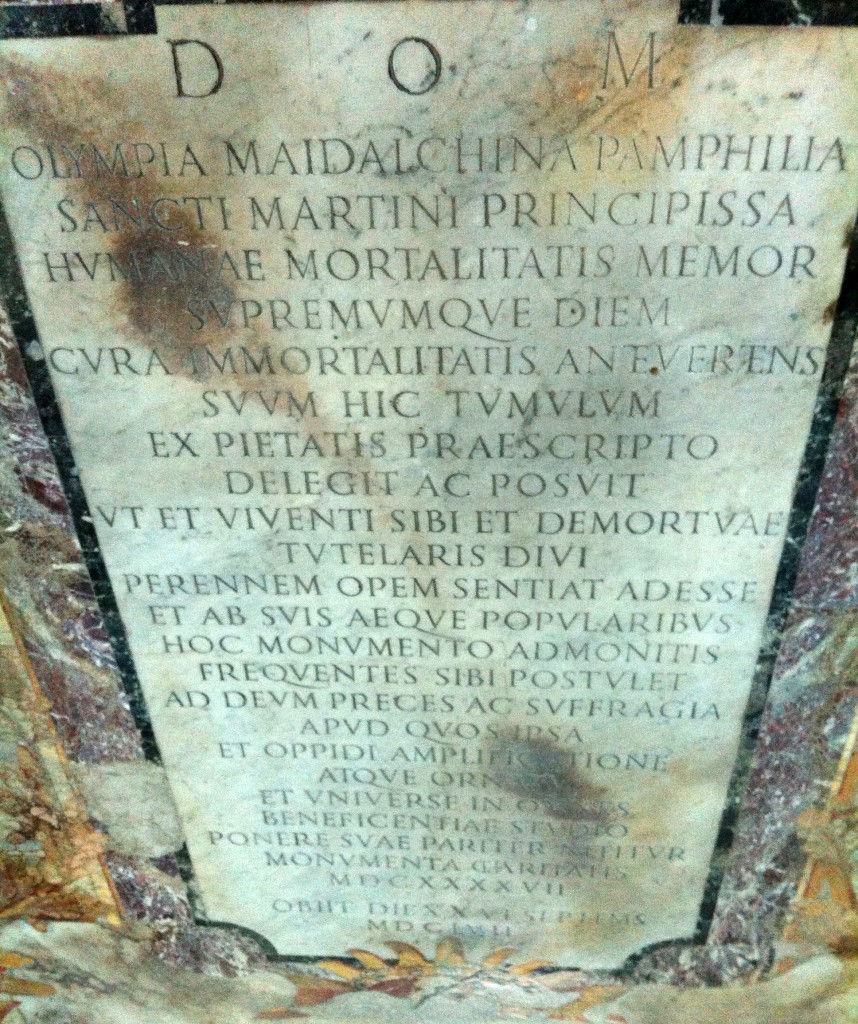

#16. PAGE 231: DEATH OF DONNA OLIMPIA MAIDALCHINI PAMPHILJ

Thanks to my Roman friend, Dr. Leonardo Tondo, I give you here a photograph of the inscription on the simple tomb of Donna Olimpia in the church of the village of San Martino al Cimino (Viterbo), the Pamphilj fiefdom which she helped to re-design and which she ruled as “Principessa di San Martino.” Of note in the inscription is the absence of reference (as is usual in funerary inscriptions) to any grieving relative as the one who saw to her proper burial and memorialization — not surprising given that she was universally hated, even by her family, it would seem. Instead, it was Donna Olimpia herself who made the plans for her burial:

#15. PAGES 232-33: BERNINI’S CHURCH OF SANT’ANDREA AL QUIRINALE (and the JESUIT NOVITIATE COMPLEX)

See as well: Joannes Terhalle, S. Andrea al Quirinale von Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rom: Von den anfängen bis zur grundsteinlegung. Weimar: Verlag und Datenbank für Geisteswissenschafen, 2011.

Terhalle’s is a comprehensive, detailed study, which publishes much new primary source documentation. Please note, however, that the correct first name of Jesuit cardinal, Sforza Pallavicino, is Sforza, not the inexplicable “Pietro” that someone a long time ago gave him and which Terhalle repeats. Someone long ago probably assumed that the “P.” found in front of his name was an abbreviation for “Pietro,” whereas it is the abbreviation for his clerical title, “Pater” or “Padre.” Too many scholars have simply repeated and thus perpetuated this error. I am happy to report that my letter on the subject to the U.S. Library of Congress was successful in getting them (and in turn, the British Library) to correct their own entry on Pallavicino.

#14. PAGES 237: BERNINI’S ROLE IN THE GAULLI COMMISSION FOR THE CEILING FRESCOS IN THE CHURCH OF THE GESU

the most recent discussion thereof is: Jacopo Curzietti, Giovan Battista Gaulli: La decorazione della chiesa del SS. Nome di Gesù (Rome: Gangemi, 2011), pp. 41-51.

The Nave Ceiling Frescos, Church of the Gesu, by Gaulli, with contributions from Bernini (photo: F. Mormando)

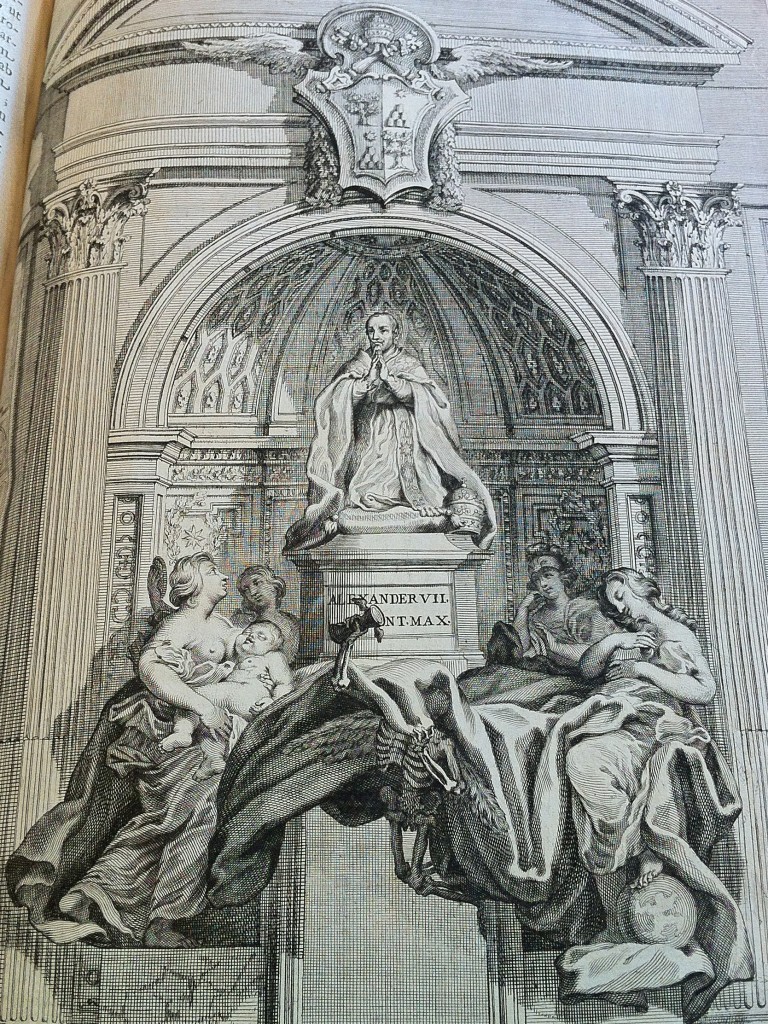

#13. PAGE 238: POPE INNOCENT XI ORDERS COVER-UP OF NUDE STATUE ON TOMB OF ALEXANDER VII

Forgive the typo: the allegorical statue covered up by Pope Innocent XI was that of “Truth,” not “Charity.” The statue of “Charity” was allowed by Pope Innocent to remain bare-breasted as Bernini intended; however, sometime later it too was covered up. When or by whom it was ordered to be covered is not known. An engraving of the Alexander VII tomb included in the lavishly illustrated volume on the history of St. Peter’s, the Numismata summorum pontificum templi Vaticani fabricam indicantia (at times referred to as the Templi Vaticana Historia) published in 1696 by Jesuit Filippo Buonanni (Bonani, in Latin) shows the “Charity” still uncovered (tabula 37, p. 93, Rome: “Ex typograhia Dominici Antonii Herculi [i.e., Antonio Herculano] 1696, et iterum Anno Magni Jubilaei 1700”):

#12. PAGE 254: COLBERT’S CRITICISM OF BERNINI’S LOUVRE DESIGN

on p. 254, I say: “Colbert found many things wrong [with Bernini’s Louvre design] on all fronts” — yes, all fronts EXCEPT, as I explain on the next page, stylistic: that is to say, contrary to what you will frequently enough read in the Bernini literature on this question, no where in the documentation is any element of any of Bernini’s five Louvre designs ever crticized for its artistic style, namely, for being “too Baroque,” “too extravagant” or “too Roman.”

#11. PAGES 257-58: THE HARROWING EXPERIENCE OF CROSSING THE ALPS OVER THE MT. CENIS PASS

One of the oft-cited letters of the famous Horace Walpole gives us an extremely vivid, first-hand account of the frightening experience of crossing the Alps, confirming my own description: the letter is dated November 11, 1739, written from Turin to Richard West. (Walpole, by the way, says it took 8 days to get from Lyon to Turin, 4 of which were spent in crossing the Alps.) The letter can be found in any collection of Walpole’s correspondence, which has been published several times. In the London 1798 edition of The Works of Horace Walpole, Earl of Oxford, 5 vols., available through Google Books, it can found in vol. 4, pp. 431-32.

For further information about the practicalities of crossing the Alps in the seventeenth century (routes, difficulties, terrors, etc.), see Laurent Bolard, Le voyage des peintres en Italia au XVIIe siècle (Paris: Realia / Les Belles Lettres, 2012), pp. 36-39.

See the 1755 drawing by George Keate (1729-97), A Manner of Passing Mount Cenis (British Museum), showing a traveller being borne across the Alps in a sedan chair carried by two porters (cat. 50, p. 100) in the exhibition catalogue, Grand Tour: The Lure of Italy in the Eighteenth Century (London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1996).

The Keate drawing is also accessible through the online site, “The Correspondence of James Barry,” edited by Tom McLoughlin, as a gloss (footnote 6) to Barry’s letter to Edmund Burke, dated September 24, 1766, Turin, which describes his crossing of Mt. Cenis (“up and down the horrid ridges of the mountains, and sometimes in the most gloomy vales between them”).

How long did the crossing of the Alps — i.e., from Lyons to Turin — via the Mt. Cenis Pass? Six to eight days, according to an 18th-century detailed guide, “Advice on Travel to Italy,” by William Patoun, c. 1766, published in A Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy 1701-1800, compiled by John Ingamells (New Haven and London: The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 1997), pp. xxxxviii.

#10. PAGE 258: REGARDING POET-LIBRETTIST GIOVANNI LOTTI

My caption to figure 29 says, “It is not known what favor or service Bernini expected from Lotti.” However, I now think that this might be possibly a reference to the poems being written by Lotti in celebration of Bernini’s Cathedra Petri in St. Peter’s basilica and his colonnade of St. Peter’s Square. Given the public outcry against the vast expenditures represented by these monumental works, Bernini would have much appreciated such excellent PR in the form of elegant verse written by Lotti, a well-known poet and respected erudito of contemporary Rome.

In his sonnets on Bernini’s works, Lotti characterizes them as the apex of the papacy’s artistic-architectural ambitions; in praising the works, Lotti also praises the genius of Bernini: see Thomas Frangenberg, “Giovanni Lotti on a lost work by Bernini,” Burlington, v. 144, n. 1192 (July 2002), p. 434. For the poems themselves, see Giovanni Lotti, Poesie latine, e toscane, ed. Ambrogio Lancellotti [Lotti’s nephew], Rome, 1688, pt. 1, p. 8 (“Alle glorie del Signor Cavalier Bernino per la Cattedra di S. Pietro illustrata da lui di più sublime sito, e ornamento, e per l’ammirabil Teatro di Colonne nella Piazza dil gran Tempio Vaticano”) and p. 9 (“Per le Statue di Bronzo, che sostengono la Catedra [sic] di San Pietro”).

Since biographical information about Lotti is hard to come by, I summarize what his nephew Ambrogio tells us of his life in the “Vita dell’Autore” that accompanies the aforementioned anthology of Lotti’s poetry. He was of Tuscan origin, born in Ripamarance (today’s Pomerance, Val di Cecina). Orphaned of his parents, he was sent to study in Bologna, thanks to the patronage of Antonio de’ Medici. After completing those studies, he moved to Naples, ingratiating himself with the social and literary elite of that kingdom. After an unspecified amount of time, he moved on to Rome where he entered the service of Cardinal Antonio Barberini, Jr., through which he developed a friendship with Giulio Rospigliosi, playwright-prelate and future Pope Clement IX. His years in Rome — where he remained for the rest of his life — were marked by public success as poet and “erudito” (scholar). He died at the age of 83 (from some other, unfortunately now-forgotten source I found his date of death as 1688), as a member of the Colonna household which he served as tutor to the children of the Conestabile.

#9. PAGE 268ff: PERRAULT AND BERNINI: A NEW REVISIONIST VIEW

An important article in the scholarly journal, Renaissance Studies (v.27, n.2, June 2013, pp. 356-70): “Perrault’s memoirs and Bernini: a reconsideration” by Jeanne Morgan Zarucchi of the University of Missouri at St. Louis. In it, Prof. Zarucchi gently takes me and other scholars to task, who simply followed without question the judgement of Cecil Gould’s 1982 Bernini in France, and have painted a thoroughly negative view of Charles Perrault as Bernini’s nemesis in Paris who worked hard to defeat Bernini at Louis XIV’s court. By reading with fresh, impartial eyes exactly what and how Perrault says about Bernini in his Memoirs and by comparing his accounts with those of other, more pro-Bernini primary sources (e.g. Chantelou’s diary), Zarucchi persuasively shows that in fact such a negative view of Perrault is unsustainable.

Though, of course, we do not know what Perrault said and did outside of what he chooses to tell us in his Memoirs — the existence of the anti-Bernini cabal at the French court is affirmed by Chantelou and it is hard to imagine that Perrault simply stayed clear of it — I still am convinced by Prof. Zarucchi’s well-researched argument that Perrault, as she says, “may in fact be a reasonably reliable witness in regard to Bernini’s character and personality” (I, in fact, doquote Perrault extensively in my Bernini, having believed that there was at least a kernel of truth in what he said, even if colored by his supposed opposition to Bernini). Furthermore, Prof. Zarucchi concludes, there is not enough evidence to characterize Perrault — as I do (Bernini, 268) — as “a leading member of the French cabal organized to defeat Bernini at court.”

#8. PAGE 272: INTENDED ROYAL RECIPIENT OF PAOLO BERNINI’S CHRIST CHILD SCULPTURE

Please correct my lapsus: the intended recipient of the sculpture was indeed, King Louis XIV’s wife but her name was Maria Teresa, daughter of King Philip IV of Spain and Elizabeth, daughter of King Henri IV of France. Henrietta Anne was the wife of Louis’s brother, Philippe, the Duke of Orléans, known simply as “Monsieur.” Maria Teresa is correctly identified as Louis’s wife on p. 245. The error on p. 272 was discovered during the process of compiling the Index when the corrected page proofs had already been sent to the printer; it was supposed to be corrected by the printer, but was not. This explains why in the Index under “Marie Thérèse (Maria Teresa), Queen of France,” you will find a citation to both pp. 245 and 272.

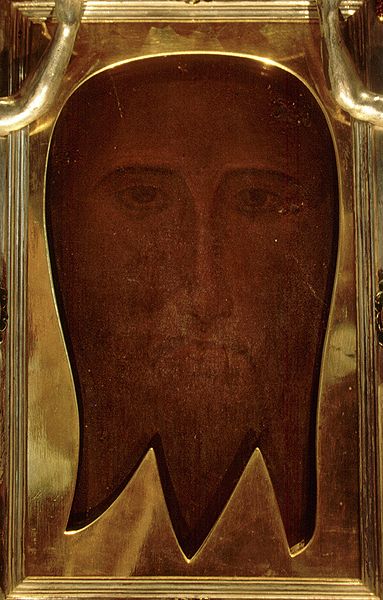

#7. PAGE 280: TRANSLATION OF “VERO RITRATTO DI VERO CRUCIFIXO”

Some scholars translate this literally as “the true portrait of the true crucifix,” whereas I believe the proper translation is “the true likeness of the Crucified One (i.e., Jesus Christ)”.

I believe Bernini’s (and Perrault’s) contemporaries would have readily understood this as a reference to the famous holy relic of the so-called “true likeness” of Jesus, several different versions of which were (are) found in different parts of Christendom, East and West, known by various names: the “Vera Icona,” the “Volto Santo,” the “Mandylion,” and “Veronica’s Veil,” the latter referrring to the pious legend according to which Jesus impressed his likeness upon the veil used by Veronica to wipe his face on the way to his crucifixion. For Bernini, the most familiar and perhaps the authentic “true likeness” of Jesus was the relic preserved in St. Peter’s Basilica in one of the four piers under its dome, deocrated by Bernini himself in the 1620s, and bearing the statue of St. Veronica.

Moreover, to translate the word “crucifixo” as “crucifix” begs the question: Which “true crucifix”? There was no such thing. A crucifix is a cross bearing a corpus, that is, a representation of the body of Jesus in some medium (ivory, metal, paint, etc.). Minus the corpus, the object is called simply a “cross,” in Italian, “croce,” as in the name of the Roman Basilica of “Santa Croce in Gerusalemme,” which housed a relic, that is, a piece of the “true cross” supposedly found by St. Helena in the 4th century. St. Helena is honored in yet another of the four piers under the cupola of St. Peter’s decorated by Bernini, this same pier housing yet another piece of the “true cross.” As Catholics well knew, the “true cross” found by Helena had long been splintered into hundreds of pieces scattered as relics across all of Christendom.

#6. PAGES 284-88: The Destiny of Bernini’s Equestrian Statue of Louis XIV

see “Bernini Updates 1” update #42, for further details.

#5. PAGES 304-05, Bernini’s “Blood of Christ” (Sanguis Christi) drawing

for further bibliography, see n. 27 in the Domenico Updates section (“Bernini Updates I”).

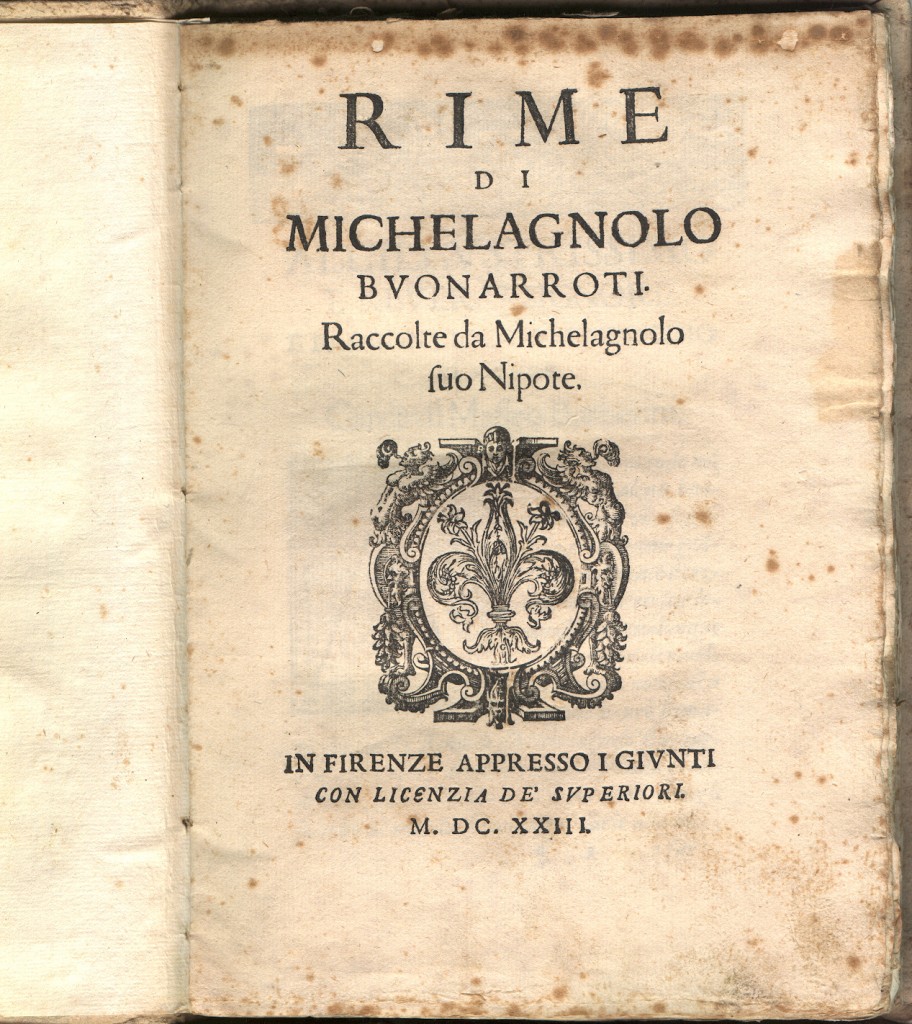

#4. PAGE 309: the 1623 editing of Michelangelo’s homoerotic poetry by his grand-nephew, Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger

For the latest detailed discussion of the extensive “reputation-saving” revisions of Michelangelo’s love poetry in the first published edition by his grand-nephew — who removed any homoerotic allusions and any less-than-completely orthodox religious language — see Janie Cole, Music, Spectacle and Cultural Brokerage in Early Modern Italy: Michelangelo Buonarroti il Giovane (2 vols., Florence: Olschki, 2011), pp. 39-45 (see n.71 on p. 42 for other detailed discussions of this well-known fact).

#3. PAGE 331: BERNINI AND WATER

On page 331, mention is made of Bernini’s being granted authorization to draw water from the public water supply to feed a private fountain on his property in Via della Mercede. New research by Katherine Rinne (The Waters of Rome: Aqueducts, Fountains, and the Birth of the Baroque City, Yale UP, 2010, pages 185-186) now shows that Bernini had earlier received access to personal use of the public water supply as part of his “reward” for aqueduct restoration for Pope Urban VIII: “When the [Aqua] Felice restoration was complete, Urban gave Gian Lorenzo an oncia of Felice water . . . Then, between 1640 and 1642, Bernini received another twelve oncie of Felice water, which he could use however he pleased, as part of his payment for the Triton and Bee Fountains in Piazza Barberini.”

For more on the hydraulic history of Rome from antiquity onward, see Rinne’s website, Aquae Urbis Romae: the Waters of the City of Rome.

#2. PAGES 341-42: BERNINI’S FEAR OF DIVINE JUDGMENT

A further reminder of the pervasive element of fear of God in the popular preaching and catechesis of early modern Roman Catholicism is this passage from St. Ignatius Loyola, a saint very familiar to Bernini:

“Although serving God our Lord much out of pure love is to be esteemed above all; we ought to praise much the fear of His Divine Majesty, because not only filial fear is a thing pious and most holy, but even servile fear — when the man reaches nothing else better or more useful — helps much to get out of mortal sin. And when he is out, he easily comes to filial fear, which is all acceptable and grateful to God our Lord: as being at one with the Divine Love.” – St. Ignatius Loyola, The Spiritual Exercises, “To have the true sentiment which we ought to have in the Church Militant,” Eighteenth Rule (trans. Elder Mullan SJ, 1914).

Christ the Judge, apse mosaic, National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, Washington DC. Lest anyone think the Vengeful, Wrathful God of the Old Testament has really disappeared; this is his 1950s Aryan version — muscular, blond hair, blue eyes! (photo: F. Mormando)

#1. PAGE 389: Add to the Bibliography

Zirpolo, Lilian H., “Christina of Sweden’s Patronage of Bernini: The Mirror of Truth Revealed by Time.” Woman’s Art Journal 26 (2005): 38-43.