OTHER NEWS, RESEARCH DISCOVERIES & INSIGHTS ABOUT BERNINI AND HIS ROME

#37. The Baldacchino restored. November 2024. Photos by Franco Mormando

#36. A Small but Excellent Exhibit of 2023: Bernini privato

The “casa museum” of the Fondazione Paolo e Carolina Zani located in the comune of Cellatica (prov. of Brescia), mounted a small exhibit in 2023 worthy of our attention: Bernini privato: la forza e l’inquietudine (here is its 135 pp. catalogue: Bernini privato exh cat 2023 Fondazione Zani.)

Essays are by Fabiano Forti Bernini (who lent several items from his personal collection), Massimiliano Capella (who describes the Baroque items in the Casa Museo Zani), Francesco Petrucci (with two essays: one on the small fresco by Bernini of St. Joseph and the Child Jesus in Palazzo Chigi, Ariccia; and the other on Bernini’s small replica works in bronze), and finally several catalogue entries on the Bernini paintings — or Bernini-attribution paintings — included in the exhibit. Having recently published an essay reconstructing Bernini’s painting collection (Journal of the History of Collections, 34:1, 2022: 33-50), I found the section of the catalogue to be of most interest to me.

Since I am not a painting connoisseur, I cannot comment in any authoritative way on the attributions. I would only make a couple of minor points.

In the first entry, Ostrow does not make reference to the St. Sebastian inventoried as part of Bernini’s private collection after his death (see Mormando, 2022, cat. 44) and in fact this latter painting is larger in height (6 x 2.5 palmi) than the one here exhibited and may have been by an artist other than Bernini, although it is not to be excluded that it is another original by Bernini. The St. Sebastian of the Zani exhibition is identified as that by Bernini (as it seems to me to be) present in the collection of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, as per the 1649 inventory of that collection. Instead — let me mention this for the record — the painting discussed by Ostrow in entry #3, Samson (or possibly David) and the Lion, less convincing to my eye as by Bernini himself (the same opinion of Tomaso Montanari and Ostrow here), does not appear among the paintings inventoried as part of Bernini’s collection at the time of his death.

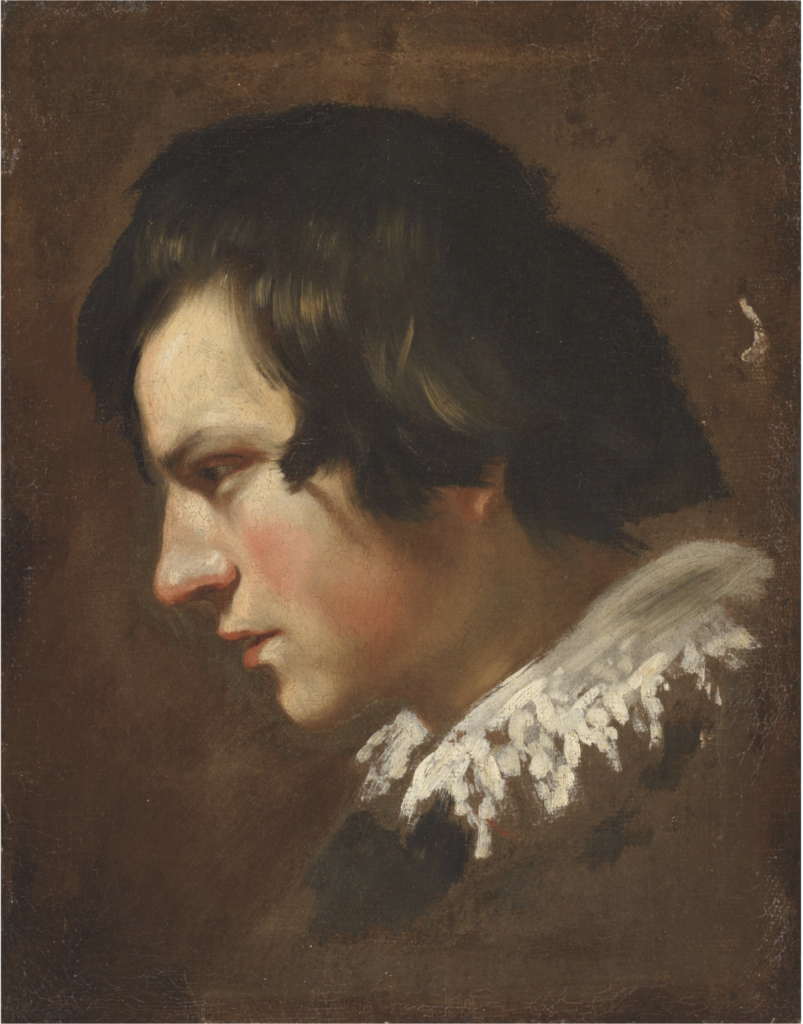

The fourth and final painting entry is by Francesco Petrucci, one of the deans of Bernini connoisseurs and scholars, who presents a new painting, which he attributes to Bernini as perhaps a portrait of the Jesuit Father, Martino Martini, a long-term missionary in China, who, Petrucci opines, could have had this portrait executed during one of the his brief returns to Rome (specifically ca. 1655): see photo below. With all due respect for Petrucci (all of whose work I highly respect and admire), I would never have guessed that this painting were by Bernini, had I encountered it before its attribution to the artist: I see no close counterpart in terms of style to any of the painted works more securely attributed to Bernini. Equally importantly, one must ask: of all the Jesuits known to Bernini, why would he have chosen to take the time from his extremely busy schedule to do a portrait of Martini? They were not friends or associates; indeed, Martini appears nowhere in the vast Bernini sources in any context whatsoever. What claim would he have had on Bernini’s precious time, especially since after the death of Urban VIII, the artist executed very, very few paintings? It is doubtful that anyone in a position of power — the pope, a cardinal, the Jesuit Superior General — would have forced him to do so. It is relevant to point out that Bernini never did portraits of the much more important celebrity-Jesuits Kircher, Bartoli, or Oliva and indeed turned down Sforza Pallavicino’s request for a frontispiece for his published history of Trent.

#35 What do we call him? Bernini’s Baptismal Name

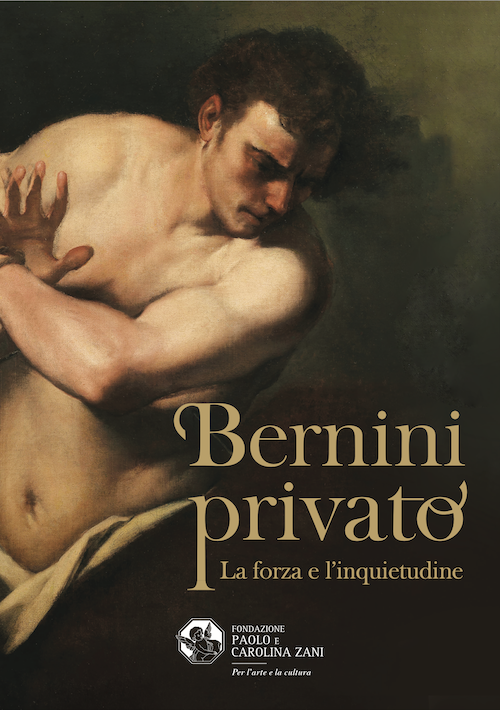

In all my publications on Bernini, I use the most familiar, common form in use today of the artist’s name, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and not “Gio. [i.e., Giovanni] Lorenzo Bernino,” as one usually finds in contemporary documentation. Family names were often treated as adjectives in early modern Italy; the forms “Bernini” and “Bernina” (as in “Casa Bernina”) are also encountered in the documents.

Bernini himself usually signed his name as “Gio: Lorenzo,” as we see above in the autograph marginal note to a letter written in Bologna while en route to Paris by Mattia de’ Rossi to son Pietro Filippo Bernini in Rome.*

The artist’s baptismal name is at times given in the primary sources simply as “Lorenzo” (such as in Jesuit Father General Oliva’s official missive of April 23, 1665, to Jesuit superiors announcing the trip to France by “Laurentius Berninus” [see Chantelou diary, f.85, n.4]). The latter usage – not a rare occurrence in the Bernini literature – I suspect, may reflect the artist’s own favoring of the name of his primary patron saint, Lawrence (and not Saint John): see Domenico, 15; and Chantelou diary, August 10, f.111, e.109.

Hence I have not heeded the call by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco (Berniniana, 2002, 50–51; Immagine al potere, 2001, “Avvertenza,” vii) for adoption of what he considers the more historically correct rendition of Bernini’s first name as “Giovan Lorenzo.” I have found one (slightly later) exception to Fagiolo dell’Arco’s statement that the form, “Gian,” is nowhere encountered in the sources: Lione Pascoli’s Vite de’ pittori, scultori e l’architetti moderni (1730–36) refers to him throughout as “Gianlorenzo.”

It is of relevance to point out that the aforementioned contemporary Giovanni (“Gio.”) Paolo Oliva’s name was indeed rendered in print as “Gian,” as on the title pages and elsewhere in some of the volumes of his Prediche dette nel Palazzo Apostolico, Rome, 1659–74. It is even more relevant to point out that, analogously, far more often than not, in early modern Italian sources, the baptismal name, Giovanni Battista, is routinely and more simply rendered as “Giambattista.”

*By the way, while we are discussing baptismal names, it is incorrect to call Bernini’s Monsignor son “Pier Filippo” or “Piero:” this usage is Tuscan and comes from the Florentine Baldinucci’s 1682 biography of Bernini, which follows Tuscan orthography and grammar. I highly doubt that anyone at home in Rome called him anything but Pietro.

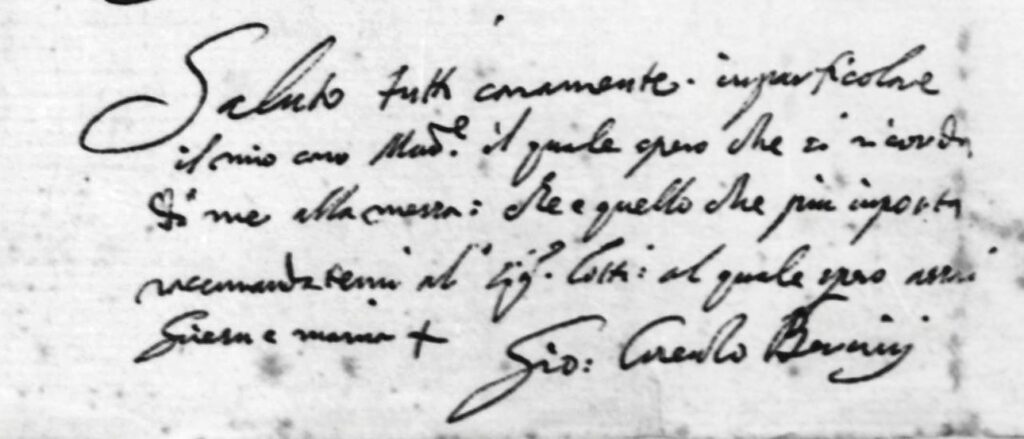

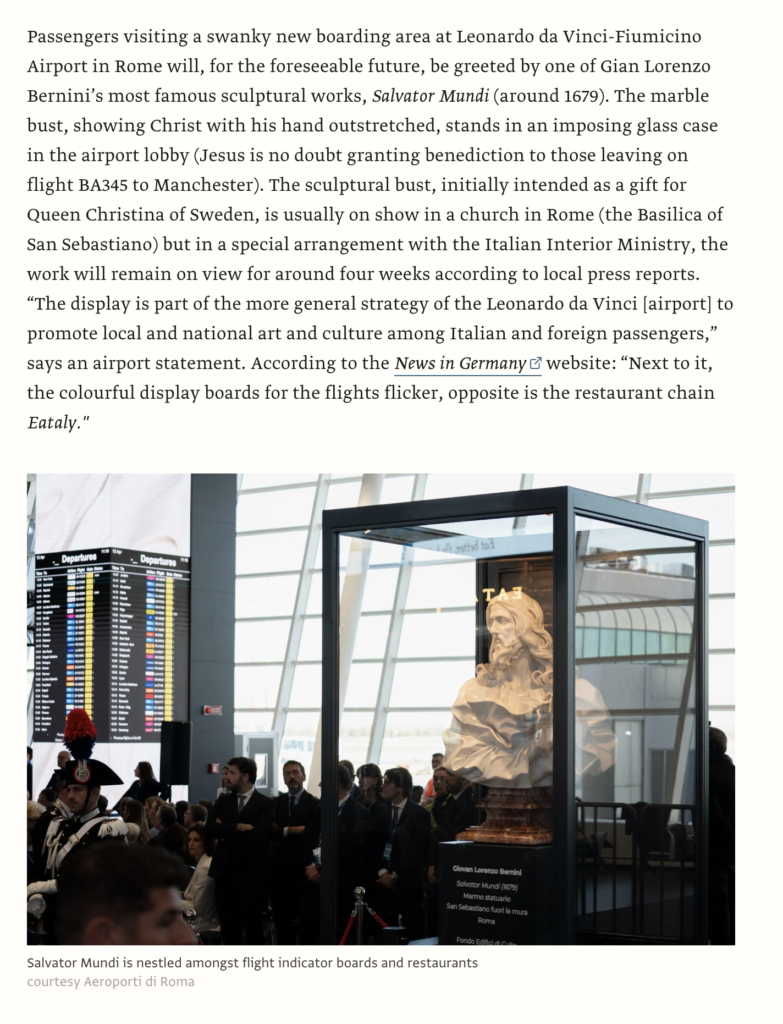

#34. Bernini at Fiumicino Airport! (published in TAN April 18, 2023)

#33. The Birth of the Modern Rehabilitation of Bernini’s Reputation

After the long years of undisguised critical disdain for Bernini and the Baroque in the 18th and 19th centuries, the very beginnings of the modern rehabilitation of Bernini’s reputation coincided with the publication of Stanislao Fraschetti’s comprehensive, meticulously documented biography of the artist, Il Bernini. La sua vita, la sua opera, il suo tempo (Milan: Hoepli) that appeared in 1900. Still an obligatory reference work for the many primary documents transcribed within, Fraschetti’s praiseworthy biography still, however, contains explicit traces of the neo-classical anti-baroque aversion to what is perceived as the “excesses” of Bernini’s style, especially his later works.

A decade later there appeared a second important but nowadays forgotten scholarly monograph whose aim was to foster, with openly declared deliberation, the rehabilitation of Bernini’s name, and which it here behooves us to remember and acknowledge: Le Bernin (Paris: Librairie Plon, 1911) by French art historian Marcel Reymond (1849-1914). It is noteworthy that Reymond’s book was published in the series, “Les Maîtres de l’Art,” which, as the title page declares, was “published under the high patronage of the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts” of the government of France. In the Introduction (pp. 7-8), we read (my translation):

“It has been a long while since we have revised these [negative] judgments [of the vehemently anti-Baroque critics of the eighteenth and nineteenth century] as far as the French masters of the seventeenth-and eighteenth centuries are concerned and have rendered the justice due to the great artists of the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV; but we have not yet done the same for the Italian masters who were their predecessors, and in particular for Bernini, the leader of that school that flourished so brilliantly in Italy and throughout Europe. Still today many people in France, on the basis of what they have read in travel guides, believe that it is fashionably acceptable to speak ill of Bernini. We wish to contribute to repair so great an injustice and to show that Bernini was an admirable artist, interested equally in the beauty, variety, and originality of his works, the greatest genius that Italy had known since Michelangelo.”

#32 Bernini’s Final Illness: A Medical Doctor’s Opinion

In the penultimate chapter of his biography (Chap. 23), Domenico describes in detail the final (and edifyingly pious) days of Bernini, “snatched away from life” by an “apoplexy,” that is, a stroke of some kind. A reader of my edition of Domenico who is a medical doctor, Dr. Richard Dasheiff, was kind enough to offer his professional opinion on the matter of Bernini’s final illness (personal communication, March 11, 2023), for which I most sincerely thank him:

“PP. 231 & 232 describe his final illness and apoplexy which initially caused his right (dominant) hand to be paralyzed, yet he was still able to converse, but was eventually deprived of his speech (but not his ability to think and gesture with his left hand). As usual with Domenico, the actual interval implied by ‘eventually’ is not quantitated, And as usual, Baldinucci (p. 430n.51 – endnote #15) concurs on the witty remark despite a paralyzed right arm (not only the hand), and in fact he reports Bernini’s entire right side is paralyzed.

Here is an opportunity, as a Board Certified neurologist, to provide a historical medical opinion for any future errata (web or 2nd edition). There are three types of strokes: small vessel, large vessel, hemorrhagic. A small vessel lacune could cause right sided paralysis, but not loss of speech or death. A hemorrhage would be immediately catastrophic. This leaves a large vessel such as the middle cerebral artery or one of its distal branches. ‘Broca aphasia’ is a non-fluent aphasia in which the output of spontaneous speech is markedly diminished and there is a loss of normal grammatical structure. Broca’s aphasia is typically produced by a fairly large stroke in the territory of the superior division of the left middle cerebral artery. If additional infarction occurs it can lead to brain swelling, herniation and death.

Thus, Bernini’s biographers may have again embellished, if not fabricated, Bernini’s greatness by having him continue to speak and be witty when he should have been immediately aphasic with the onset of his stroke.”

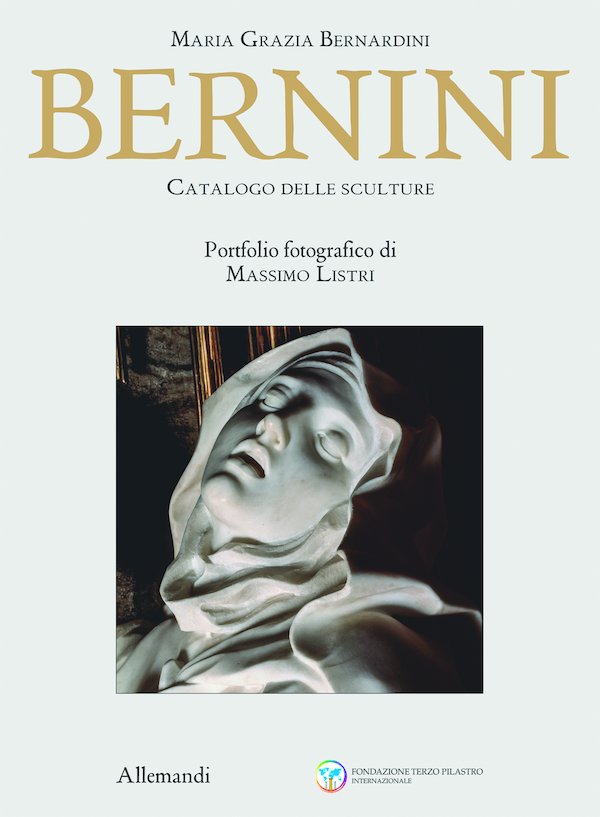

#31. A monumental new work on Bernini:

Maria Grazia Bernardini’s magisterial, comprehensive, meticulously documented catalogue raisonné of all of Bernini’s sculpture has just been published. In two volumes, 650 pages, with succinct but wide-ranging, judiciously worded entries on each work, in addition to complete bibliographies and excellent photography. It without a doubt supplants Rudolph Wittkower’s catalogue in all respects. (There are a couple of surprises in the section, “Opere attribuite o di attribuzione controversa.”)

#30 18th-century Anglican echoes of Bernini’s “Blood of Christ” composition

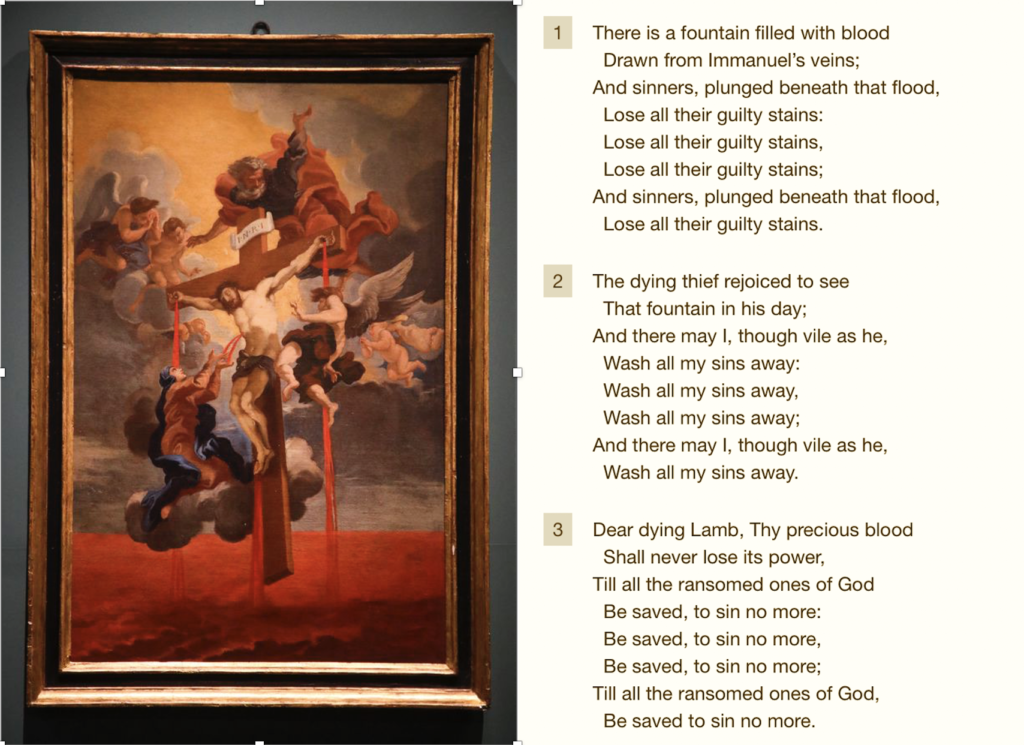

I have at times come across disparaging references to Bernini’s “Blood of Christ” composition (a drawing transformed into painting by Guglielmo Cortese and others, derived from a vision of St. Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi) as rather gory and so typical of over-wrought Roman Baroque Catholicism. The scene certainly does not appeal to me but judgements about its being so quintessentially Roman Baroque need to be emended when we compare the image to the lyrics of a famous Anglican hymn, “There is a fountain filled with blood,” written by popular English poet and hymn-writer, William Cowper (1731-1800):

Bernini’s “Blood of Christ” image juxtaposed with William Cowper’s hymn, “There is a fountain filled with blood.”

#29. How unverified claims about Bernini pass down through the decades by scholars who do not stop to check and question their sources:

Was Bernini a member of the elite Congregazione dei Nobili at the Gesù?

Early in my academic training, I learned never to unquestioningly accept the historical (or other) claims of an author, no matter how prominent he or she is, without checking the sources they cite. I started doing this immediately when embarking upon my Bernini studies in the year 2000 and was surprised — at times shocked — how baseless or otherwise unverified claims about Bernini have been repeated, not only in the popular press (such as in the case of the anti-Inquisition legend surrounding the elephant monument at Piazza Minerva), but also, and more seriously, in formal, serious scholarship. One example regards Bernini’s supposed membership in the elite “Congregazione dei Nobili dell’Assunta” based in the Chiesa del Gesù in Rome. (This confraternity still exists: their stemma is in the photo above.) Let me illustrate the problem in detail.

I happened to first came across this piece of information in the otherwise fine article by Maria Grazia D’Amelio, “La magnificenza del ponte. Funzione e rappresentazione nel Ponte Sant’angelo a Roma nel XVII Secolo” (in La città e il fiume (secoli XIII-XIX), ed. Carlo Travaglini, pp. 169-80. Rome: École française de Rome, 2008). Therein D’Amelio states (p. 170, n. 7) as a fact that both Bernini and “his friend,” Giulio Rospigliosi (future Pope Clement IX) belonged to this confraternity, and cites as her source, Marina Minozzi, “La decorazione di Ponte Sant’Angelo” (in Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Regista del Barocco. I restauri, ed. Claudio Strinati and Maria Grazia Bernardini [Milan: Skira, 1999], pp. 77-84). (D’Amelio, by the way, does not cite a specific page for this information, and one is obliged to go fishing for it in the entire article: this is not good scholarly form.)

My first reaction to this claim was skepticism: Bernini was not a member of the nobility, so how could he belong to a confraternity very famous for its very noble members? One would have to suppose that his rank as “Cavaliere” granted him eligibility, but the sodality’s statues do not state this explicitly. However, if he did belong, this eminent pious (and socio-economic) fact would certainly have been worthy of being publicized in the very hagiographic biographies by his son Domenico and Baldinucci. In any event, I located the claim in Minozzi’s article: in her note 22 on page 79, she cites as her source for the claim as “Castellani 1954, passim.” More skepticism on my part: What? This Castellani refers several times — “passim” — to Bernini’s membership? More inexact scholarship (but, again, in another otherwise fine article). The answer is No, as I discovered in consulting “Castellani 1954,” that is, Giuseppe Castellani, La Congregazione dei Nobili presso La Chiesa del Gesù in Roma; Rome: no publisher given (!), 1954. What I found in Castellani is described in the relevant footnote to my edition of Domenico’s biography (p. 266, n. 149), which I here reproduce (slightly abridged):

Castellani’s 1954 history of another pious congregation at the same church of the Gesù, that of the “Nobili” (Nobility) or the “Assunta” (its formal title is “Congregatione della gloriosissima Vergine Assonta”), lists Bernini as a member as of 1640 (Castellani, 273. Mullan’s 1918 history of the same congregation makes no mention of Bernini, either as member or benefactor). Castellani cites no source for his information and one wonders about both the veracity of his claim and the state of extant documentation: Why, e.g., is Bernini only one of five individuals explicitly listed by Castellani as members in the long period 1617-97 in an inventory claiming to list all known members from 1593 to 1954? Bernini was, furthermore, not a member of the nobility and hence technically ineligible, if the entrance criteria, re-promulgated in 1629 (Castellani, 164, “siano nobili in quel grado, che si ricerca”), were taken seriously, as Maher, 251-52, says they were in the first half of the seventeenth century. The 1629 Rule (Regole) and Customs (Consuetudini) books of the congregation also mention nothing about almsgiving nor of dowries to unwed poor girls (not even those given on its patronal feast of the Assumption) of which Domenico, 171-72, makes much in his description of his father’s favorite forms of charity. It also seems strange that neither Domenico nor Baldinucci (nor any other source) makes note of his membership in what was an extremely prestigious sodality, known especially for its sponsorship of the lavish Forty Hours devotional spectacles at the Gesù: see Mullan, 115-125; and Castellani, 189-90, for their sponsorship; … see Maher, 248-59, for the most recent research on the history of the Congregation of the Nobles. It is pertinent to note, finally, that neither congregation (the “Bona Mors” and the Nobili) is mentioned in Bernini’s last will and testament.

Moral of the story: scholars, young and old, please do not repeat claims without checking to see that your sources are creditable!

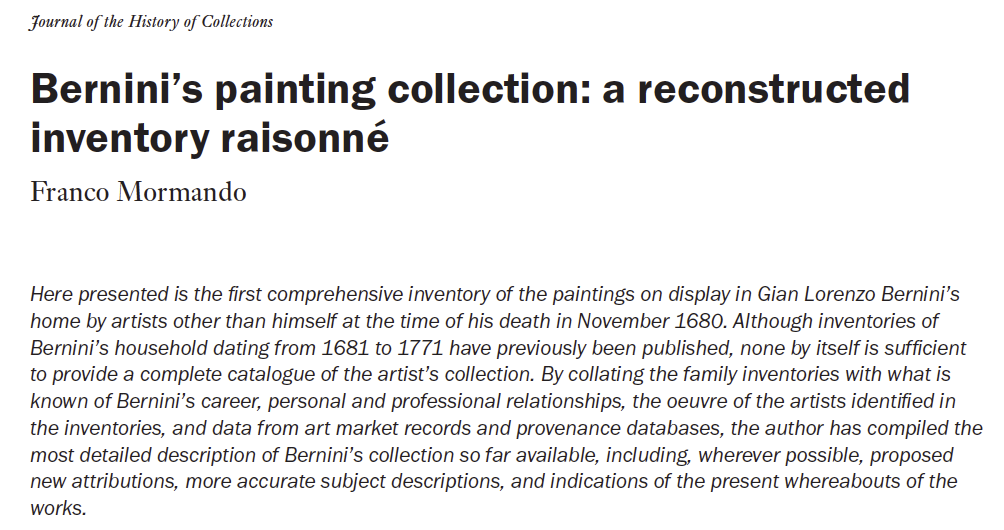

#28. Bernini’s Painting Collection

At the time of his death, Bernini had on display in his home about 60 paintings by artists other than himself, inventoried in at least 4 family documents, the first dated January 1681. I have done a detailed study of this collection, which adds much to our knowledge of Bernini’s taste in art and collecting habits. The article has been published in The Journal of the History of Collections vol. 34, n.1 (March 2022): pp. 33-50. Here is the first page of the article: Mormando Bernini Painting Collection Page 1

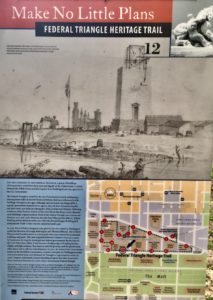

#27. “Speak to me of nothing small!” From Baroque Rome to Washington DC

Visitors to Washington DC might come across this historical marker recounting the construction of an even grander and more “magnificent” government center in the city (today known as “Federal Triangle”), under the direction of “visonary” architect, Daniel Burnham (1846-1912), chair of the McMillan Commission (the Congressional committee tasked with executing the project). To Burnham are attributed the well-known words of instruction and encouragement regarding the embellishment of Washington DC, “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood. Make big plans.” (The words are quoted towards the bottom of the historical marker in the photograph.)

The sentiments behind the remark harken back to the architectural theory of Baroque Rome and more specifically to the stark admonishment by Bernini to the assembled members of King Louis XIV’s court on June 4, 1665, on the occasion of the artist’s first meeting with the king himself that day: “Speak to me of nothing small!” (Bernini and His Rome, p. 267). Bernini assured Louis that he would design a royal residence far more magnificent than all those he had seen en route from Rome to Paris. It is a great tragedy that that vision of urban planning was lost in the post-World War II period and its vandalization of the structures of the “City Beautiful” movement of the late 19th- and early-20th centuries, the greatest act of vandalization being the destruction of McKim, Mead and White’s Pennsylvania Station in New York City to build that monstrously ugly and utterly dehumanizing Madison Square Garden.

#26. A Bernini Workshop Portrait Bust of Pope Urban VIII

Portrait Bust of Pope Urban VIII, attributed to the Bernini workshop, formerly in the Lord Weidenfeld Collection. (Photo: Christie’s)

I recently happened to come across on the internet this “repoussé parcel-gilt copper bust” of Urban VIII, attributed to the Bernini workshop, sold at Christie’s, May 17, 2017, sale 13756, lot 569, from “The Collection of the late Lord Weidenfeld GBE.” The accompanying “Lot Essay” reports: “The present head derives from possibly the earliest bust Bernini made of the pontiff, just after his accession in 1623. Wittkower suggested this bust, now in San Lorenzo in Fonte, Rome, was executed by Bernini with the help of Giuliano Finelli, who joined Bernini’s studio in 1622 (Wittkower, op. cit., p. 185). The present head is seemingly identical, with allowance for the surface differentials between carved marble and copper repoussé. This head is unique in Bernini’s series of busts of Urban VIII in the absence of the papal camauro, a tradition that Bernini instigated in around 1630.”

This website describing the very small church of San Lorenzo in Fonte contains a link to a photograph of the bust from the online “Fototeca” of the Fondazione Zeri of Bologna. I myself do not quite see any close convincing relationship between the head of the San Lorenzo bust and that of this former Weidenfeld bust, but one would have to see the two busts side by side in person. In any event, my intention here is simply to record the existence of this bust, and not make a judgement about the attribution. Note, however, that the bust ended up selling for below (i.e., 25,000 British pounds) the initial estimate of its value (30-50,000 British pounds).

#25. A Goat Head by Bernini in the Torlonia Collection?

1st-century Roman statue of a resting goat whose head is attributed to Bernini (image: FondazioneTorlonia.org )

The famed Torlonia collection of antiquities has been much in the news recently on the occasion of the opening of a special exhibition at Rome’s Capitoline Museum of a large selection of newly restored items from the family’s collection, long inaccessible to the public. And all of the news reports of this exhibition that I have read do not fail to mention the ancient statue of the “Resting Goat” whose head, they say – following what the Torlonia collection website itself claims (without citing any documentation) – was sculpted by Bernini as part of the statue’s restoration when it belonged to the Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani (1564-1637). Alas, there is no documentary evidence at all to justify this claim.

Yes, it is a very finely executed head indeed, and we do know that Pietro Bernini did some restoration work for Giustiniani, but no documentation of any restoration work for the family by Gian Lorenzo has yet surfaced. However, in an article, “Bernini Father and Son as Restorers for Vincenzo Giustiniani: A Venus and a Goat,” included in the 2021 exhibition catalog, The Torlonia Marbles: Collecting Masterpieces (ed. Salvatore Settis and Carlo Gasparri; Milan: Electa, 2021, pp. 92-97), Tomaso Montanari argues for a firm attribution of the goat head to Gian Lorenzo (dating it to circa 1620), based on similarities with the workmanship of other early pieces, specifically, the treatment of the eye in the Camilla Barbadori Barberini bust (Copenhagen, c. 1619) and the treatment of the hair in so-called Anima dannata (c. 1619, Rome: Spanish Embassy to the Holy See).

Note that, as Montanari reports, the first time Gian Lorenzo’s name was ever attached to this goat head was in 1876 by Pietro Ercole Visconti who compiled the Catalogo del Museo Torlonia di sculture antiche of that year; previous to that it had been attributed to Algardi (i.e., by Vincenzo Pacetti in 1793 in his Inventario della Raccolta Giustiniani).

#24. Bernini Drawing Sells for $2.3 million

A Bernini drawing (56 x 42.5 cm.) representing a study of a male nude sold in France for 1.9 million euros / $2.3 million US, on March 20, 2021 (lot 100). The sale price was far above the original auction estimate of 30-50k euros, set by northern French auction house, Actéon in Compiègne.

#23. Sale of Hester Diamond’s “Autumn” statue

Allegory of Autumn, attributed to Pietro Bernini with contributions by Gian Lorenzo. (Photo: Sotheby’s)

The marble allegorical statue of “Autumn” (height 49 ½ in.; 125.5 cm.) from the collection of the recently deceased Hester Diamond of New York City has sold at Sotheby’s for $8,881,500 USD. It has been attributed to Pietro Bernini, with contributions from Gian Lorenzo, although what those specific contributions might be has never been a matter of consensus among Bernini scholars. It is completely undocumented, except for the fact that at some point we know it entered the collection of Leone Strozzi (d. 1632) and remained with that family (Villa Strozzi) until sometime in the 19th century. I would assume that inasmuch as a depiction of one of the four seasons, this piece has three long-missing companions.

In any event, such allegorical figures were typically done to adorn gardens and hence were not of the highest quality. For all we know, Pietro may have had other assistants contribute to the execution of the statue. As for its date, the Sotheby’s catalogue gives circa 1615-1618, whereas distinguished Pietro Bernini scholar, Hans-Ulrich Kessler, author of the first (and only) magisterial catalogue raisonné of Pietro’s work (Munich, 2005, p. 355, cat. C3) dates it earlier, i.e., to circa 1614-1616. This dating makes sense since shortly after 1616 Gian Lorenzo was to produce the magnificent Saint Lawrence statue (Madrid), which shows a superior hand nowhere evident in this “Autumn” work. The same can be said for the hypothesized — and superior — Gian Lorenzo contributions to the early Satyr Molested by Putti (Metropolitan Museum, NY).

#22. Painting attributed to Bernini on art market

Portrait of a Young Man in Profile, oil on paper, laid down on canvas, private collection, now on the art market (Christies, Online, Sale 18877, lot 133, 26 Nov-17 Dec 2020). The “Lot Essay” accompanying this painting in the Christie’s catalogs refers to Bernini’s “taste for the unfinished.” We have to keep in mind that many of his paintings were unfinished either because they represent studies, trials, and experiments while Bernini was learning the art of painting or because they were just pleasant “pastimes” for Bernini. Their experimental or casual nature also accounts for the variety of style we sometimes see in paintings attributed to Bernini, (who, by the way) never considered himself a painter (as is noted, for example, in the Chantelou Diary and elsewhere [see p. 263, n. 120 of my edition of Domenico Bernini’s Life of Bernini]).

Update: the painting sold for 50,000 GBP (US $69,502): the link above publishes the result.

#21. Bernini’s Portrait of Pope Clement X

To really appreciate the design of Bernini’s portrait of Clement X (now on display in the Galleria d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome), one must remember that it was commissioned for a very specific site, a high niche overlooking the library of his family’s Roman residence, the Palazzo Altieri (Piazza del Gesù). The photo below shows the bust in its original location before its removal to the museum.

Bernini, Pope Clement X Altieri, Rome: Palazzo Barberini (foto: F. Mormando)

The library, Palazzo Altieri, Rome showing Bernini’s portrait of Pope Clement X in its intended location (photo: Massimo Listri)

Jan Kraek, Portrait of Maria Apollonia of Savoy (recently on art market, photo: artnet.com)

#20. Did Bernini design the funerary monument of Princess Maria Apollonia, the “Infanta of Savoy”?

Alexander VII’s Diary has two entries (Oct. 22, 1662 and March 11, 1663) in which he records discussions of designs for the tomb of Maria Apollonia of Savoy (1594-1656) with Bernini. This has long led scholars to reasonably believe that he indeed had a role in its design. Extant documentation specifies the names of those involved in the execution of the project, but does not name the author of the design nor the overall supervisor of the project. However, the fact that the execution was principally the work of Gabriele Renzi, a member of Bernini’s workshop, would also argue in favor of Bernini’s role in the design. Though she died in Rome, Maria Apollonia’s simple tomb is in the basilica of San Francesco in Assisi, where by her wishes (she was a devout member of the Franciscan Third Order) her remains were finally deposited in 1662.

Maria Apollonia was the daughter of duke Carlo Emanuele I of Savoy and Catherine of Hapsburg (also known as Catherine of Austria, daughter of King Philip II of Spain). For the question of Bernini’s role in this tomb, see note 77, p. 193, in Mascia Meleo, “La collezione dei ‘preziosi’ di Maria di Savoia. Doni e dispersione dell’eredità sabauda da Innocenzo X Pamphilj ad Alessandro VII Chigi,” in Ori nell’arte: Per una storia del potere segreto delle gemme, ed. Stefania Macioce (Rome: Logart Press, 2007), 185-187, 191-193.

#19. Bernini the (occasional) art dealer

We are led to believe that Bernini, like many of his artist contemporaries, may have occasionally played the role of art dealer by one note in the travel diary of French visitor to Rome, Bathasar de Monconys, who in May 1664 purchased from “the pope’s sculptor” – and this, we presume, is Bernini, given that it is the reign of Alexander VII – a bacchanal of “petit enfants” (i.e., putti) by Poussin and two works of imperatore size (most assuredly, landscapes) by Claude Lorrain: see his Journal des voyages de Monsieur de Monconys Conseiller du Roy . . . Première Partie, Paris, 1677, p.459 (Troisiéme Voyage d’Italie). The paintings in question have not, to my knowledge, been identified among those extant by Poussin; shown above is one of the two bacchanals of putti at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica (Palazzo Barberini), both much smaller in size that the quadro da imperatore here in question.

#18. How much is a Bernini drawing worth?

Bernini, Design for Funerary Monument, ca. 1640 (photo: Christie’s, NYC, Jan. 28, 2020 catalog)

A relatively small drawing (21.4 x 19.8 cm) by Bernini, fully autograph and previously published, has sold for $75,000 at Christie’s New York, January 28, 2020 (lot 32). It represents a sketch (of ca. 1640) for a never executed funerary monument, featuring Death standing by an open, occupied sarcophagus, with instructions by Bernini about its execution.

#17. How much is a small Bernini replica worth?

Bernini (workshop): The Blessed Ludovica Albertoni (photo: Sotheby’s, NY)

A small bronze reproduction (19 x 44.8 x 176 cm.), coming directly from Bernini’s workshop, of the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni recently sold for $572,000 USD, well above the original estimates. The piece has its provenance in the collection of the Palazzo Altieri (it was the Altieri who commissioned Bernini’s marble statue in San Francesco in Ripa). It sold at Sotheby’s, New York, “Master Paintings and Sculpture Day Sale” (Sale N10309, lot 267, “Property of a European Private Collector), January 30 2020, 10 am.

#16. Two Bernini exhibitions in the same season in the same country:

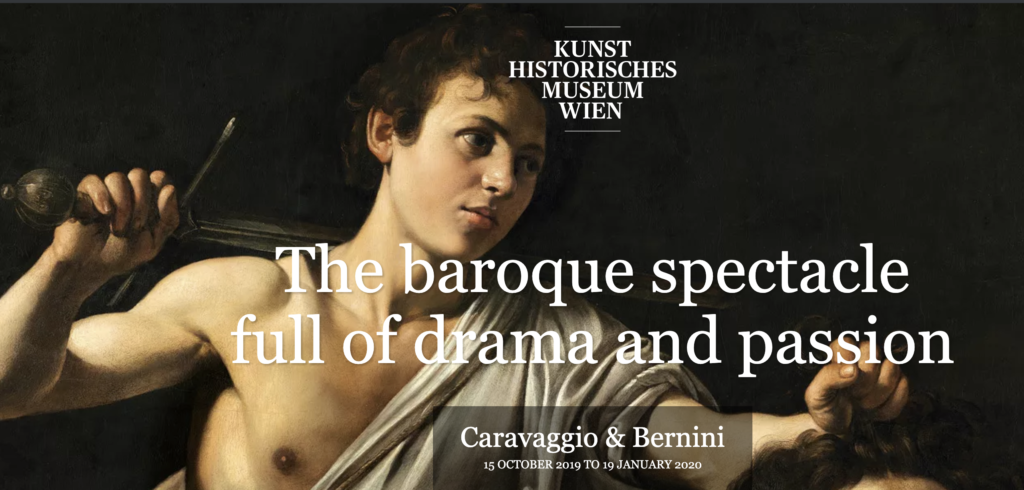

. . . in Vienna, “Caravaggio and Bernini” (long ago art historians decided that Bernini and Caravaggio were in two, separate, opposing camps: not true! Bernini absorbed elements of Caravaggio’s style – especially the use of theatrically dramatic lighting – and finally a public exhibition is drawing attention to that fact:

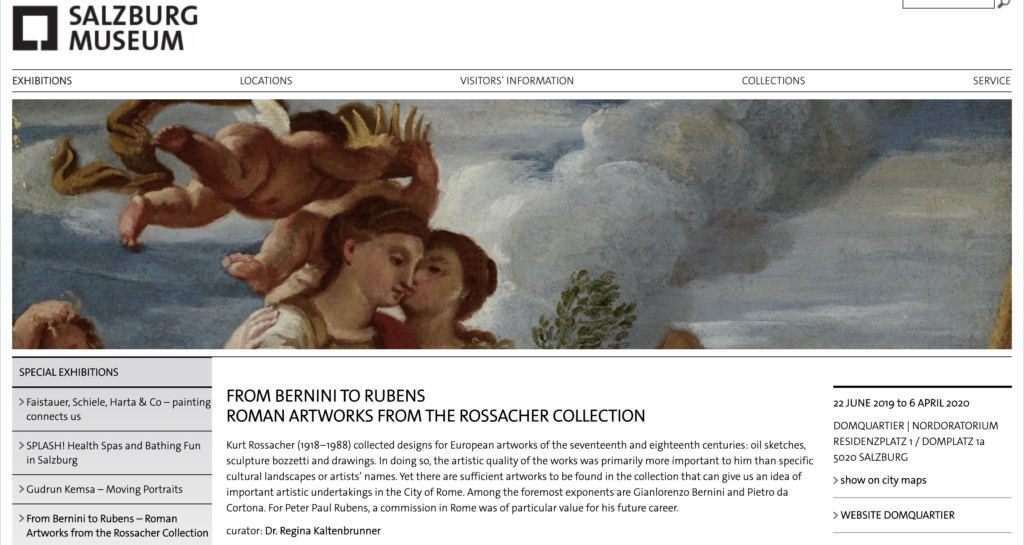

. . . and Salzburg (alas, however, the attributions of the clay models in this collection to Bernini are still the subject of debate):

And, by the way, while we are on the subject of artistic juxtapositions, it would be great if there were an exhibition devoted to Bernini and his northern counterpart and older contemporary, Peter Paul Rubens (1570-1640). As far as I know, only one scholar has treated the subject in more than cursory fashion, Charles Scribner III, in a talk charmingly entitled, “Rubens and Bernini: Artists Who Did Not Starve.”) and more formally in a paper simply entitled but richly informative and insightful, “Rubens and Bernini.”

P.P. Rubens, Self-portrait, 1623, Royal collection, UK (foto: Wikimedia)

#15. Bernini’s Bronze Portrait of Pope Urban VIII on Art Market

- Bernini, Portrait of Pope Urban VIII (1658 casting)

A 1658 casting of Bernini’s portrait in bronze of Pope Urban VIII (d. 1644) from the Corsini collection of Florence, has been placed for sale at the Galleria Carlo Orsi of Milan. The work was originally in the Barberini family collection in Rome (duly listed in the family inventory) and corresponds to the bronze portrait in the Louvre commissioned by Cardinal Antonio Barberini for Louis XIV in 1656. (My thanks to Dr. Charles Scribner III for having brought this news to my attention and having supplied the summary provenance note, saving me the time and trouble of going through my own Bernini database.)

Update: The Galleria Orsi does not list the purchase price of the bust and I have not been able to discover that information (or any other information about the sale); however, this article about the Galleria Borghese’s attempt to raise money to purchase the bust mentions that they were aiming to collect $8 million. By law, the bust could not be sold to anyone or institution outside of Italy.

UPDATE: The 2019 sale apparently did NOT happen for some reason, for it was subsequently placed on display in the Palazzo Barberini, Rome in 2023, still described as the property of Prince Corsini. (Here’s another notice of that same 2023 exhibition.)

#14. Long-lost portrait of Donna Olimpia by Velazquez is rediscovered

Portrait of Donna Olimpia by Velazquez

A work not seen since 1724, the portrait by Diego Velazquez of Donna Olimpia Maidalchini Pamphilj, sister-in-law and former lover — as whispered about by and through all of Rome — of Pope Innocent X re-surfaced in Amsterdam last year and having been restored and authenticated, is up for auction at Sotheby’s London, July 3, 2019, lot. 28. The exquisitely executed portrait does nothing to sweeten the image of “La Papessa,” who is to be greatly admired, if not perhaps loved, for her success in the vicious male-dominated arena of Baroque politics and society. (It was purchased from Olimpia’s estate, by the way, by the famous Spanish royal representative in Rome and Naples, Don Gaspar Méndez de Haro, 7th Marqués del Carpio, Duque de Montoro, Conde-Duque de Olivares, Marqués de Eliche (1629 – 1687), a great collector of art who also owned some works by Bernini.

#13. Where was the Vatican Foundry in Bernini’s time?

People have asked: Where exactly was the Vatican foundry (Fonderia Apostolica) where Bernini spent a lot of his time when at work on the Baldacchino and the Cathedra Petri? On this corner of the 1618 map of Rome by Matthias Greuter (†1638), you will find it, encircled, in the upper left, above the capital letter A, safely isolated in a field by itself, lest any explosions or other fires emanating from it damage nearby buildings. In the lower right there are other, smaller kilns, fornace, that also serviced the Fabbrica di San Pietro, not far from the “Santa Marta” neighborhood where the Bernini family lived from sometime after August 1629 (date of his father’s death, after which the family moved to Santa Marta) until their new and permanent move to Via della Mercede in 1642. (For a modern edition of the Greuter map, by the way, see Roma nel Primo Seicento: Una città nella veduta dei Matthäus Greuter, ed. Augusto Roca des Amicis; Rome: Artemide, 2018.)

#12. A newly discovered portrait by Bernini:

A newly discovered portrait (oil on canvas) by Bernini – now in the Aso Tavitian collection, New York City – Portrait of Young Man (Domenico Bernini Senior?) – has been published by Tomaso Montanari in his La Libertà di Bernini (Turin: Einaudi, 2016, fig. 60 and pp. 188-95), seconding the attribution made earlier by Erich Schleier (Montanari, 2016, 188, n. 79). On the back of the canvas are clear indications that the work once belonged to the 7th Marquès del Carpio, Gaspar de Haro y Guzman, who was Spanish Ambassador to Rome (1677-82; thereafter Viceroy of Naples, 1682-87), during which time he came to know Bernini and his family. (For the Marquès del Carpio, see my Domenico edition, p. 299, n. 19.) The 1682 inventory of Carpio’s art collection (compiled shortly before his transfer from Rome to Naples) includes a “portrait (testa) of a young beardless man by the hand of the Cavalier Bernini” that had been given to him by “Monsignor [Pietro Filippo] Bernini.”

(The portrait was included in the exhibition at the Clark Institute, Eye to Eye: European Portraits 1450-1850.)

Domenico makes no mention of this gift, but instead records (p. 28) the gift of a pencil drawing / self-portrait by Bernini that he [Domenico] gave as a gift to the Marquès. Montanari (2016, 194) speculates that the sitter may be Bernini’s brother, Domenico (who died in 1656), citing the fact that in the second Bernini family inventory of 1706 the portrait by Bernini of the said Domenico, recorded in the 1681 inventory, no longer appears and had presumably left the family collection – that is, as conjectured by Montanari, given away to Carpio. The 1681 inventory describes the portrait as a quadretto, a small painting, as indeed this newly discovered canvas is. Assuming that the sitter is indeed Domenico Senior, who therein appears to be around 12 years old, Montanari (2016, 194) dates the canvas to around 1629.

#11. An answer to the question raised of my book: “Why so much scandal about Bernini, his family, his patrons, and in general, the Rome of his lifetime?:” see my article published (October 11, 2012) in the online journal, Berfrois: Intellectual Jousting in the Republic of Letters.

#10. The Intellectually Dishonest Professional Book Review:

“This happens ALL the time:” In a public lecture at Boston College (April 12, 2012), Sam Tannenhaus, editor of the New York Times Book Review, responded to my question about what editors like he do when they receive a badly written, intellectually dishonest, irrationally negative book review, i.e., one that is logically incoherent, makes assertions without proof, and is full of jaundiced “cheap shots” against the book or author. “This happens ALL the time,” replied Tannenhaus. To hear his complete answer, view the video on BC’s “Front Row” (his answer begins at minute 23:30).

#9. Two common complaints of reviewers of this book:

1. “There are not enough illustrations:” It was my publisher who put a limit on the number of images that I could include in the book. I would have wanted many more.

2. “There is not enough detailed discussion of Bernini’s individual works of art:” As clearly stated in my Preface, this is not meant to be an art historical discussion, or a Bernini “art appreciation” guidebook; there are many such books already in circulation. Rather, my work focuses, as no other book in English has done in the past, on Bernini the flesh-and-blood human being and his historical context.

As a matter of fact, my original manuscript did include more discussion of the individual works of art, but I was obliged by the publisher to reduce the size of the text. In the course of his long lifetime, Bernini produced hundreds of art works: it would take 1000 pages to do justice to even just the most famous of them.

It is, nonetheless, a puzzle to me that, whereas virtually no one who writes a biography of a literary figure, such as Shakespeare, would ever be expected to give a summary and/or analysis of each of his plays or poems, the biographer of an artist is somehow under an obligation to treat the artist’s works of art, as if the works of an artist are somehow more revelatory of his or her psyche and personal life than the literary works of a poet or playwright! They are not.

#8. Preface, Bernini: His Life and His Rome as the “first English-language biography of the artist:”

This claim is accurate: if someone finds evidence to the contrary, I would be happy to receive it.

Please note Howard Hibbard’s Bernini (first published by Penguin Books in 1965 and still in print) is NOT a biography and was never meant to be one: it was written as a discussion of Bernini’s career as sculptor. Note what the author himself says in the “Foreword” therein: “In the following pages I have tried to present Bernini’s sculpture in an an organic, which is to say chronological order…. My hope was to give some idea of the growth and development of Bernini’s artistic vision. In order to do this it was impossible to confine the text to a discussion of sculpture alone, although I was asked to write specifically about that aspect of Bernini’s work. There is a vital connexion between Bernini’s sculpture and his architecture. I have not approached the buildings as an architectural historian, but rather tried to show how Bernini’s architecture arises out of his novel approach to artistic problem.” In other words, this is an art historical-critical exposition of Bernini’s work, not his life, that is, it is an account of the sculptor and architect, not of the man, even though there is some biographical data sprinkled in here and there.

#7. Bernini: His Life and His Rome, page 25: Bernini’s home parish, Sant’Andrea alle Fratte:

The church, “St. Andrews in the Thickets,” was inadvertently omitted from my Index. In any case, note that in seventeenth-century documentation the church’s name appears both as “alle Fratte” and “delle Fratte,” with the former — it would seem — more common than the latter until the eighteenth century when it all but disappears giving way to today’s single form, “delle Fratte.” For the designation, “alle Fratte,” see, for example: Rudolfo Grimming, Sedici pellegrinaggi per le 365 chiese di Roma (Rome: Ghezzi, 1665); Filippo Titi, Studio di pittura scoltura et architettura nelle chiese di Roma (Rome: Mancini, 1674) and Giuseppe Vasi, Indice istorico del gran prospetto di Roma (Rome: Pagliarini, 1765).

The Church of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, late 16th century construction, most famous for its belltower by Borromini (slightly visible in the upper left). In Bernini’s time it was run by the Order of the Minims of St. Francesco da Paola.

#6. Bernini as Guest of Marchese Riccardi in Florence (Domenico, 124-25):

As Domenico and Baldinucci both observe, while in Florence, Bernini was guest of Marchese Gabriello Riccardi, chief steward to the granducal court in early May 1665 en route to Paris. In 1659 Riccardi had purchased from the Grand Duke the Palazzo Medici in Via Larga (now Via Cavour), which was being expanded and embellished in the 1660s when Bernini came to town. Bernini presumably slept in this palazzo during his three-day visit. However, in order to view the Riccardi collection of antiquities, he also visited the other (and original) Palazzo Riccardi, which, as Baldinucci observes in his Life of Bernini, was in “Via Gualfonda.”

Thanks to the kindness of my friend and long-time resident of Florence, Dott.ssa Francesca Avezzano-Comes, I came to learn (during my own recent visit to Florence) that “Via Gualfonda” is today’s “Via Valfonda” (alongside the Stazione di Santa Maria Novella) and that Palazzo Riccardi still stands at #9, the headquarters of the “Confindustria Firenze”). Here is a photograph of the building:

#5. And on the topic of the Riccardi family and Bernini:

The Altes Museum (the Old Museum of Antiquities and Sculpture) in Berlin owns an ancient Roman piece that used to belong to the Riccardi of Florence, but was sold to the Germans in 1842: Head of Singing (or Talking) Dionysius (marble, Roman, after an original from 279-250 BC). I have not yet been able to verify that this head was indeed in the collection at the time of Bernini’s visit, but it is a nice coincidence that the work is one of the “speaking likeness”type, that is, a “portrait” of the subject in the act of speaking (or here, perhaps singing), a dramatic moment that Bernini himself liked to capture in stone in his portraits:

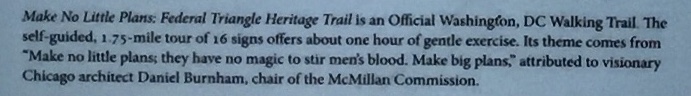

#4. Bernini: His Life and His Rome, page 351: “If you seek his monument, just look around you:”

This final line of my book in the unabridged first draft of my manuscript had the following footnote, which was omitted in the final version due to space considerations:

“This is the epitaph of English architect, Christopher Wren (whom we met briefly in Chapter 5), written by his son. The original is in Latin: ‘Si monumentum requiris, circumspice.’ It refers to London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, a work of Wren’s design and his burial place. It has since been applied to many an architect, but to whom is it more applicable than Bernini and ‘his’ Rome?”

#3. Regarding Bernini and King Charles I:

Francis Haskell’s The King’s Pictures: The Formation and Dispersal of the Collections of Charles I and His Courtiers (Yale University Press, 2013) reports (p. 89) that, for the purposes of public auction (after the king’s beheading), Bernini’s marble portrait bust of English King Charles I (later lost in the great Whitehall fire of 1698) had the great distinction of being officially valued at 800 pounds, a figure “higher than any other piece of sculpture in the royal collection, including antique sculpture.”

* * *

The royal exhibition, In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion organized by The Queen’s Gallery, displayed both the original triple-portrait of the king by Anthony van Dyke (now in Windsor Castle) used by Bernini to execute his marble portrait of Charles and a contemporary marble bust of the king (attributed Jan Blommendael, 1650-1707) that gives some idea of the lost Bernini original.

Unfortunately, the text and reviews relating to the exhibition perpetuate two undocumented stories that have long circulated about Bernini and Charles I: there is absolutely no proof that Bernini, upon receiving the king’s portrait in Rome, made a remark to the effect that “this was the portrait of a doomed man.” The other error is the claim that the bust was a gift from Pope Urban VIII to his god-daughter, Queen Henrietta Maria, Charles’s wife. While the pope did grant his permission for Bernini to do the work, the work was a direct commission from the English royal family, who paid for all of the (exceedingly large) expenses involved, including cost of marble, labor, and transportation.

David Howarth identifies the origin of the legend about Bernini’s remark about the king’s portrait: “Isaac Disraeli, littérateur and father of the Prime Minister, summoned up the ghost of things past when we wrote, with apparent no foundation in fact, of Bernini’s reaction to the Van Dyck triple portrait as it was unveiled in his studio: ‘he [Bernini] exclaimed that he had never seen a portrait whose countenance showed so much greatness and such marks of sadness: the man who was so strongly charactered and whose dejection was so visible was doomed to be unfortunate.'” (David Howarth, “Bernini and Britain,” in Effigies and Ecstasies: Roman Baroque Sculpture and Design in the Age of Bernini, ed. Aidan Weston-Lewis [Edinburgh: The National Gallery of Scotland, 1998, 29-36, here 30-31], quoting Richard Ollard, The Image of the King: Charles I and Charles II [London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1979, 25]).

#2. An overlooked minor work by Bernini: a Design for the Sacristy of the Duomo of Tivoli?

Dec. 2, 1658: Cardinal Marcello Santacroce (created cardinal on 2/19/52; created bishop of Tivoli on 10/14/52) sends a letter to Bernini, thanking him for his design of the cathedral’s sacristy and informing the artist about the completion of the work. There is no indication that Bernini had any hand at all in the execution of his design. The letter in question is extant: Bibliothèque National de France, Paris, Ms. ital 2082, f. 60, as per Sandrina Bandera Bistoletti, “Lettura di testi berniniani…” in Paragone (Arte) 1985: anno 36, n. 429, pp. 43-76, here 59 and n. 114. In her note Bandera Bistoletti says the year on the date of the letter is hard to decipher: it is either 1658 or 1678; however, it has to be 1658 because Santacroce died in December 1674 and there is not another Cardinal Santacroce until 1699.

However, more recently, Francesco Ferruti explicitly denies Bernini’s responsibility for the Tivoli Duomo work: “Giovanni Antonio De Rossi (1616-1695, no relation to Mathia [de’ Rossi] [was] the author, for Cardinal Marcello Santacroce (bishop of Tivoli from 1652 to 1674), of the sacristy of the Cathedral and the atrium in front of it (1655-57), often erroneously attributed to Bernini himself” (my translation): see Ferruti, “Note storico-artistiche sui documenti riguardanti l’attività di Matthia de’ Rossi nel Duomo di Tivoli,” in Atti e memorie della Società tiburtina di storia e d’arte (2014) vol. 87: 153-160, quotation from pp. 153-154. Ferruti’s footnote to that claim sends the reader to: P. Portoghesi, Roma barocca (Bari, 1973, p. 921); and M.G. Bernardini, ed., Sei-Settecento a Tivoli. Restauri e ricerche (exh. cat., Tivoli, Villa d’Este; Rome, 1997, pp. 27-28). Ferruti makes no mention of the letter cited by Bandera Bistoletti, which now needs to be re-read to perhaps determine more accurately its content and intent. Did Bernini submit a design that was in reality not executed? (In any event, Ferruti’s article is not about Bernini but, as its title says, his assistant, Mattia de’ Rossi, who designed and carried out the renovation of two chapels in the Tivoli Duomo, that of the SS. Sacramento and of the SS. Crocifisso.)

#1. SO TRUE! The lack of a more complete picture in art historical scholarship:

“The history of Italian painting is normally read, or re-written, from a Catholic viewpoint; if we had a survey of Rome like the one Deborah Harkness has written about Elizabethan London, we could more easily see the secular forces at work there too…”

–Clovis Whitfield, Caravaggio’s Eye (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2011), p. 13 (Acknowledgements).